You are Here

by Kate Kimball

You don’t know his name. When the defense attorney says it, followed by a staccato of questions, it is foreign, a muddled language that your tongue can’t make its way around. It is a bullet grazing your ear. It takes you a long time to answer questions—maybe two minutes, sometimes three. You had practiced the answers for weeks. You had role-played and rehearsed. You had spent one hundred and thirty dollars on a skirt. You wore low heels, a formal sweater, simple earrings, a hint of perfume. For the most part, you looked like there wasn’t anything wrong. You looked okay. There is a way to remake the experience, your lawyer had said. There is a way to show up and say what you need to say, but this time, something is different because you are here and he is here and he is going away. No. Not like last time. He is here and after, you can leave.

There is a quiet hum in the room from the fluorescent lights and you find some space where you can step outside of yourself, leave your body on the stand, fly above and look down on the room. Even though you promised you would work on not separating from your body and use your newly learned coping skills, like breathing slowly, you can’t help it now, and do it anyway.

The jury is a mix of young and old—more men than women. You take note of the older man in the wheelchair, the woman with a hijab and shy eyes, the heavily tattooed older man, an earring in his ear. Everyone looks bored. Everyone, except a woman—older—a touch of gray in her hair. Her eyes look strained and there are moments, you note, where the attorney speaks and she looks as though she wants to spring forth and ask a question. For that reason, she reminds you of your mother.

You had almost asked your mother to come. Almost. But, your sister was getting married the same week and she was busy. Incredibly so. Your mother was serving the luncheon at the local ward house—a familiar tradition only found in Salt Lake City—something you had initially wanted to blow off anyway. You could never fit with those stereotyped Mormons. They were so happy and so calm and family-oriented. Everything was about service. Everything was about gratitude. It wasn’t their fault. Something had always bothered you about your own tribe. But now, you would give anything to be there.

We need to review that night, the attorney begins. I know this is difficult, but we need to know what happened. Can you do this?

You’re above the attorney, staring at his shoes, which you figure must be Cole Haans, and the way his hair is thinning in the back, making an odd orb on top of his head. His voice is solid and for a moment, it scares you, before you remember that you are here—up above—so high and that you need to go down and enter yourself again.

You breathe in and breathe out.

Yes, you tell the attorney. Yes.

You wish you could pray, scramble a million different fragments of prayer together, but the blood swirls around your head. Your temples throb. The pressure; the pain.

Yes.

You know this man. You know him and his cousin and his friend and how they sat on the floor snorting lines of crystal off of your driver’s license and taking turns tangling their fingers in your hair and making fun of your religion and making lewd comments about your body. At first, they took turns stuffing their fists underneath the front of your dress, rubbing fingers over your nipples and later, moving in between your legs. The cousin said you had nice hair. It was long unruly then. Now it is short—cut to your chin. Your mother says that it suits you.

The man knew your brother. He knew your brother’s name and age and workplace and all about the fishing trip taken last summer in Colorado and he knew how your brother had failed rehab twice and had moved in and out of your parents’ house so often that you could hardly count the times. He knew where you lived and he knew the shortest route to take. When he saw you walking home from school and offered you a ride, it was still light out. Early, even. You tell the attorney that it was maybe 7 pm and it was terribly cold.

November? He asks you. You wore a coat?

You have a hard time remembering what happened before. But you do remember the coat. After, it was all that remained.

You had the coat when you presented at the hospital, the attorney reminds you. Do you remember how you got there?

You had stood in the lobby of the hospital staring at a map of the many wings. There was Labor & Delivery, Pediatrics, Med/Surg, Emergency. The map was a never-ending realm of cages. It was cold, and you only had a sock and the coat, the shards wrapped tightly around your frame, mind spinning around the star on the map, You are Here, You are Here, You are Here.

Until you were not.

A man brought you a wheelchair, the attorney offers. He was a radiology tech, just off of work; he described you as being in shock. Confused. You didn’t answer him when he asked if you needed help. Everything was so fast.

How did you get to the lobby?

Of the hospital? You ask.

He nods slowly, and you try to pull yourself back in.

You breathe in and breathe out.

Before the hospital…before. You had tried to sit up, first, and it was as though you couldn’t breathe. The air was cold.

There was snow outside and burned-out Christmas lights. There was a pile of tightly rolled newspapers by the front door. There was a crack in the window, a dead spider in the sill.

How did you leave the house? The attorney asks. What happened then?

First, you threw up. It wasn’t easy, though. No. You wished for death when your diaphragm heaved. For a moment, you thought you would pass out—the pressure was so great. The broken Christmas lights. The shards of glass. You had been unable to make it to the bathroom and the vomit had been spewed messily by the wall. You had needed to go to the bathroom and hadn’t made it there, either. You remember the way you couldn’t stop even though you tried. You remember the smell.

You made it out, the attorney offers. In your statement—you mentioned the door.

Everything was about getting to the door. You moved slowly, dizzily along a hallway. Half the carpet was torn up. The wood was sharp and you worried, for a moment, about splinters. You felt terrible. You were sick.

You hadn’t had insulin for a long time…you picked up a broken bottle from the floor. You tried to smell it, but the only thing you could smell was the urine. Your purse had been gutted—messes of biology notes, a torn book by Kafka, used syringes, an empty bottle of Tylenol. Everything was turned inside out. Your wallet was gone.

Did you have a watch to tell time?

No, you say. You have no idea how long you were there.

The insulin was a concern because you knew your blood sugar was high. Your head was cloudy and you felt sticky and hot, but cold. You were freezing.

You felt hot…and cold? The attorney pauses.

Yes.

Yes, hot and sick and tired and sore, but the door was there and you could see it.

Did you try to stand?

No, you whisper. Your legs were a jellied mess and you were afraid, terribly afraid of what was on them. It was urine or spit or blood or semen or feces or vodka or all of it and more. But, you told yourself it was oil paint. It was framed up and captured. It was abstract.

Paint. In your purse, you had two tubes of oil and three brushes. The canvas you had been carrying earlier was the torso of a woman, her arm stretched in front of her breasts. You were still working on her tendons, the rope of muscle from shoulder to elbow. It was as though she was going to shoot a bow, the arrow flying ahead. Away. She didn’t have a face. But, you thought of adding one just then. You had to get it done. You had a terrible headache. But, still.

The problem was, you begin. There weren’t any clothes.

Your clothes, you mean? You couldn’t find them?

You were panicked for clothes. In the beginning, you had been walking home, snow beginning to fall. Underneath, you wore black underwear and bra. It was important to match, your roommate had said. What if you were ever in a car accident? You wore a slinky blue dress, a pair of black tights, gray boots, a thin sweater, the long black wool coat.

Did you remove your own clothes? The attorney asks carefully. Was it by choice?

The house was his grandmother’s, the man had said. She was in California visiting his aunt. In the kitchen, she had linoleum that was swirled with brown and gold. The gold, oddly, was the color of one of the paints you had purchased at the college bookstore that day. She had white ceramic jars for flour, sugar, salt. She had an elephant-shaped cookie jar. She had crocheted mismatched towels.

He offered you a beer.

No, you say. You didn’t take it. You had drunk beer before, yes. But, you had walked by the church one Sunday and had found yourself going in, watching the entire service in your dirty jeans with one earbud in your ear playing Shirley Manson. Eventually, you turned it off and crossed your legs, listening to the hymn instead. You wondered if you would ever believe.

The man told you he had never liked Mormons.

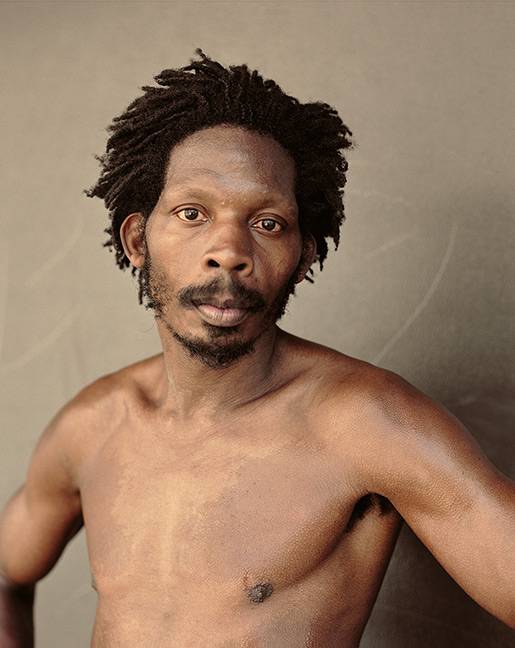

He wanted you to meet his friend. You remembered the friend’s name—Russ. He had shown up once at the bar where your brother played. Russ had long dark hair that he had formed into messy dreadlocks. He wore wrinkled t-shirts and holey jeans. His arms were so skinny that you thought they looked like they belonged on a child. There was something wrong.

But, it hadn’t been hard to get you from the car to the house. No. The man wanted you to meet Russ. He wanted to show you his paintings and he wanted to ask you about your brother’s music. He told you that your eyes were beautiful and he touched your arm, asking you to come in and stay.

You didn’t know what made you do it.

But you know that there was a piece of you that cared so much it made you reckless.

It was everything, really. It was studying chemistry and barely passing classes and losing the ability to add and subtract. It was hours and hours of studying and writing equations over and over and passing with 72% and that not being enough, never being enough. It was taking any job that came your way and making deposits of two dollars into a checking account that was on the constant verge of overdraft.

It was because you didn’t know if there was a God.

It was because your mother had told you that you choose everything in life, including how and when you die. You chose your family and the place to which you were born. You could never blame anyone; never. Everything, always, was your doing.

Did you want to go into the house?

Yes.

Because he had touched you and it meant something. Because he had touched you and told you that you had an incredible smile and because he seemed kind, you would go anywhere with him. You would do anything. You were that lonely.

Yes.

But you can’t say this aloud. No. Not here.

You took an art class that semester because it looked interesting and because you couldn’t, just couldn’t find meaning in equations. You drew naked figures of all sizes. A man with a deformed leg. An overweight woman with heavy breasts. A flat-chested Asian woman who looked like a child. You found it meaningful.

Was this the man you went inside the house on 32nd East with? The attorney points to a man you cannot look at. But, you do focus on his hands. They mimic the movement that he once had inside you, rapid, strong, agitated.

You can’t answer. Not yet. You float above and look down, heat rising to your head in embarrassment.

Do you know him?

You told him that because you were trying to change your life, you couldn’t sleep with him. Because you decided that maybe, maybe there was a God, it wouldn’t be right. Maybe there was a place for you in His kingdom, your mother close by. It didn’t matter if you went to medical school and made a six-figure income. It didn’t matter that he knew all of your brother’s songs and he thought he was a genius. It didn’t matter that you liked his laugh.

Let’s go back to the clothes.

The woman juror who reminds you of your mother seems, for a minute, interested in this. Clothes. Everything, once you moved out of your mother’s house, revolved around an avoidance of laundry.

At the time, you had impeccable taste. You spent almost every paycheck on rent, diet soda, and clothes. You bought tailored skirts made of satin and nylon. You bought heeled shoes that made you look like the woman you were not—confident, controlled, careful. There were heavy bangles, earrings made of precious stones. Cobalt blue blouses, cuffed red slacks, heavy belts. Lots of comforting blacks and alluring grays. Lace lingerie in the color of Easter grass that no one saw. You could wear something different every day for three weeks without doing laundry. At the time, this was important to you.

The man told you that he hadn’t slept in three days. He asked you to ride his wave.

He wanted you to relax, open up, let him in.

Had you ever done drugs before?

Pot, you tell the attorney. Once, soaking your feet in a bathtub in Colorado, where you went to visit your roommate’s parents. It was over Spring Break. All it did was make you cough.

The man wanted you to snort crystal. He said it would make you not feel anything. It would unleash your superpowers. You told him you wanted to leave—you had to go back to the canvas and finish the arm. This was important.

Did he let you leave?

The room feels like an aquarium. You seem to go forward, bump against glass and retract. All the heads are looking at you. You can feel their stares.

His cousin came in through the kitchen. He was smoking and he carried a McDonald’s bag. He offered you fries.

Take them, the man said, his hand crawling underneath your dress, stroking between your legs.

You didn’t. Later, you wished you would have.

The thing was, you knew and didn’t know. You knew when the man told you to take your dress off, you didn’t have an option. You knew that when Russ appeared, the gun held loosely in front of your face, you didn’t have an option. When the cousin had taken your wallet and laughed at the lack of money, you didn’t have an option. All you had was a folded twenty-dollar bill. Money for food for the week.

You still said no.

Did you try to leave? Did you try to get away?

You had never seen a gun before in your life. Your brother didn’t hunt nor did your father. Your mother thought any possession of weapons was morally wrong. She believed in the words of Chekhov. If a gun is placed on stage, it needs to go off…

You were afraid? The attorney offers.

Yes, you admit.

The truth was, even though you were an adult, even though you were in college, you had never had sex. There were men, of course. You did what they wanted to a point. You could handle the jumble of awkward limbs in a movie theater; you didn’t mind kissing or even going down on them in the dark, quiet interior of a car. But you had never been led to what was next. You held onto the idea of a temple marriage, like the one your parents had. Like the one your sister was going to have. You couldn’t be with someone for eternity if you had sex before marriage. You could never walk into the temple feeling clean.

Because you are here and the man is here, you have to talk about these things. You have to stumble through the fact that you began school with a 4.0 GPA and ended with a 2.4. Perhaps if you had more knowledge at the time, you think now. Perhaps you could have done what he wanted and left whole. Was there a real difference between yes and no? Maybe yes was all it took to erase pain.

Let’s refocus, the attorney suggests. How did you get to the door?

Staying still, you start. You fumbled along the floorboards, your palms moving your body inch by inch. At the time, you were afraid to breathe. Perhaps the clothes were there, you say. But, you couldn’t look. You couldn’t stay in the hallway.

It was very dark.

Your blindness forced you to feel everything—the urine-soaked floorboards, the wall smeared with feces, the shards of glass from the smashed bottle of vodka. Later, you managed to find your dress. In the store dressing room, it had made you like the others your mother went to church with. You were together, then. You weren’t a mess.

The dress was wet and torn. It looked like trash.

Where had the men gone?

You didn’t know. They had snorted a few lines, drank vodka from the bottle after. They laughed about the way you had cum and had hit your head into a table when you tried to resist.

Perhaps they had fallen asleep.

Did they leave?

You had prayed then. It was sloppy, poorly formed. It was not in the language of your mother. You knew that you had chosen this as you had chosen everything in your life up to this point, but you were still you and you couldn’t leave without clothes. It was just too cold.

The coat was in a heap by the door, you tell the attorney.

You don’t tell him that you thought it was an answer to your prayer.

At first, it had almost seemed like the body of the cousin, the man that had spoken to you like he knew you. You’ve always been so alone. But I hear you. I am your Savior. At night, you can’t get his whispers out of your ear.

Did you put the coat on and leave immediately?

No.

The coat was a heavy thing and it was hard to figure out the belt. You managed to pull it onto one arm and then you heaved, vomit trailing down the side of your mouth, falling on the coat. Still, you didn’t care. And later, when you kneeled and used the doorknob to pull yourself upright, you didn’t care.

Where did you go after you opened the door? Did you try to go to any of the houses in the area?

No.

You were too cold and scared and dizzy and sick. Your head pounded from being hit on the table. You felt that your body was something newly unzipped. Soon, everything was going to empty. You couldn’t think about what was between your legs. You couldn’t know.

Because it was November and it was snowing, you tried to walk quickly. The snow stung your feet and the wind scraped your face.

You are here you are here you are here.

You didn’t have direction, exactly. Your eyes hurt and it was hard to make out the signs in the dark. Were you going north or south or east or west? All you remembered was the 7-Eleven you had passed on the way to the man’s grandmother’s house. There was a payphone. There was a light. You had to get there.

But your legs hurt. Your blood was so high that there were shooting pains down your nerves. Your feet throbbed and it was hard to walk.

So, eventually…you made it to the 7-Eleven?

Yes.

Yes because you had to get home and get insulin and take a shower and lay down. Yes because there was the canvas and the stack of homework for Human Physiology and the Cell Biology final in two weeks. Yes because you hadn’t talked to your roommate for three days and because you didn’t have any money, you had to call her collect.

When your roommate came and got you, you apologized for the smell. You told her that you drank too much and wandered off. The party was lousy, you said. You didn’t miss anything.

You told her to take you home. You promised her money for gas.

She didn’t want the money and insisted that you see a doctor. Yes, she took you to the hospital and dropped you off in front. After you left four days later, you went back to your apartment and found that she had completely moved out, never to be seen again. For a while, you tried looking on Facebook. You Googled her name. No one knows where she went. She just isn’t here.

The room feels like a wave that you can’t swim through and your head pounds.

Do you know this man? The attorney repeats. He points over to the man, the man whose body moved yours in a way that covered the anger of the world. He said that he loved you. He told you that he was your salvation. I am your Savior. He talked to you like he was the truth and the light, the path to follow to find home.

The attorney breathes in, waiting.

Pieces of prayer spurt inside your mind. There is the cry for help. If only you knew what to say.

Do you know you are here? The attorney asks.

You are here and your mother is not and your sister is not and your brother is not. Soon, your younger sister will be married to a man that will do things to her, all sorts of things, but because she says yes, they will be everything this isn’t. Your sister and her husband will sleep next to each other under a quilt that your aunt sewed and whisper things, things not like you have heard, better things. There will be hope. You are here and maybe God is and maybe all you can do is pray in fragments. Maybe your language will always be haiku.

Do you know this man?

Yes, you decide after breathing in and breathing out. I do.

Kate Kimball is a PhD student at Florida State University. Her work has appeared in The Hawaii Review, Ellipsis, Weber: The Contemporary West, Kestrel, and Arcadia among others. She has worked over fifty jobs and originally is from Salt Lake City. Her work, at times, draws on these things.