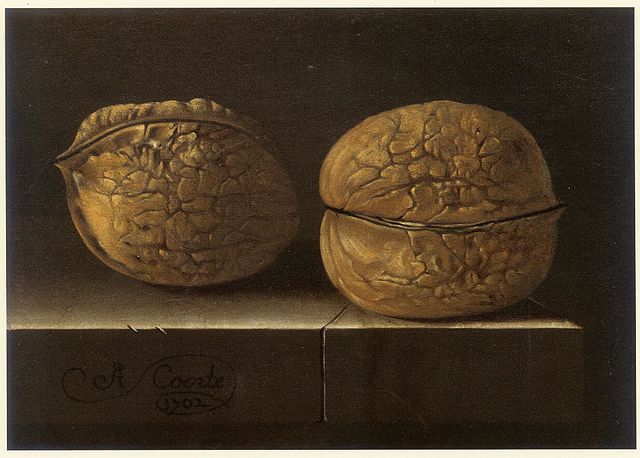

Coorte, Adriaen. Two Walnuts. 1702, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.

The Walnut Queen

by Annette Leavy

The storm woke me. Lightning had turned the night sky orange, and the wind thrashed branches from the walnut tree outside our bedroom window against the glass. Raindrops pummeled the barn’s roof—I’d never heard anything so loud and distinct and trembled like a cow in her stall.

Ezra snored and turned over, the only sign that the storm had penetrated his sleep. I didn’t want to wake him, not out of kindness or because of our long, strange day but because I believed I had caused the storm to descend on us when I’d made up my mind to visit the Walnut Queen.

La France profonde. Refurbished 18th-century stone barn. Hayloft bedroom. It had been February when Ezra found the ad at the back of the LRB.

“Let’s go.” He’d been ready to leave without packing.

“Maybe we should sleep on it,” I’d hesitated.

We had barely gotten out of the house all winter. I only went out to scurry back from errands or the gym to check on Ezra, his blood pressure, or pain meds.

“We’re too old to fight about directions,” I had said.

“There’s the GPS,” Ezra had parried.

“Last time you argued with her.” (“Why can’t you listen to her?” I’d remonstrated.), and he’d chuckled remembering.

Forty years earlier, I’d wooed Ezra with mock turtle soup, the tureen topped with puff pastry into which a baker had carved a Cross of Lorraine. In the dead of winter, I’d found us a yellow room with a sleigh bed and a view of a bend in the Moselle River. “The Cross of Lorraine,” the man I was just getting to know had laughed as if he couldn’t believe his luck.

After that first trip, we’d returned to France whenever we could, crisscrossing the countryside for its bounty—Camargue rice, Le Puy lentils, sweet wine from Saussignac, and chèvre from the Drome, hauling all we could manage off the plane—milky white faience from Moustiers and knives from Nontron; a vintner’s basket with the weaver’s initials, M.C., carved into its sturdy handle; and deco flatware, with another someone’s initials swirled within a pattern of leaves and grasses, discovered under a pile of stained linen after an hour’s rummage under a brutal flea market sun.

We always got lost and we always fought about whose fault it was. It was a young person’s sport, hunting for treasure, arguing, and falling exhausted but happy into bed, ready for more the next morning.

Now cancer and caretaking had made me timid and tentative. How could I say I’m afraid to feel old with you in France?

“Okay,” I’d agreed instead, “but no wild-goose chases, no gallivanting after goat cheese or three-hour drives for lunch.”

Delphiniums and cabbage roses were blooming in the garden when we arrived at the barn. I arranged vases for the kitchen table and the bedroom. “Lovely,” I said.

Ezra found a plum tree in fruit. “Delicious,” he said.

We hiked up the hill behind the barn every morning, and every evening we sat outside to watch the sunset over the hill. “Lovely,” we agreed.

During the day we kept our pact and stayed close to home.

“Let’s take the Route de la Noix,” Ezra would suggest and I’d smile in return—in the Périgord, every lane, main or back street was a Route de la Noix.

My husband believed in the curative power of walnuts. “Good for the heart,” he’d confer with one market stall keeper; “for arthritis,” the next.

“And for the digestion, monsieur,” the seller would reply, offering a sample in return.

Ezra seemed content, even happy, stopping to taste the offerings of each stall in every market. By the end of the first week, I was groggy from peace and loveliness, restless with longing for the lively, lusty, argumentative couple he and I had always been in France.

One night he announced earlier than usual, “I’m going to bed.” Before cancer, there would have been a kiss behind my ear and an invitation, “Come to bed.”

“I’ll stay down.” I tried returning to my novel but instead began scrolling through Le Fooding and Trip Advisor. O Plaisir des Sens—the restaurant’s name caught my eye, the promise of modern cuisine, the photo of the youthful chef and his attractive wife.

“Let’s go to La Roque-Gageac,” I suggested the next morning. “There’s a good place for lunch.”

We ate under a red umbrella. At the next table, a celebratory family quaffed champagne. Two couples, look-alike city slickers with designer haircuts and black jeans, arrived late, ordered off the menu, and leaned back in their chairs, admiring themselves.

“Good choice,” Ezra glowed pink and appreciative under the red umbrella. It had been a long time since he’d looked at me that way.

Before coffee I got up to poke around. There were hand-milled soaps and lavender in the powder room. The dining room was entirely white—walls, table linens, and bleached-wood floor—except for a primary-colored mural that filled one wall: From an oversized pot, the winking chef offered an oversized spoon to his wife, who smiled saucily back at him. “O plaisir des sens,” read the caption that came off her head.

The wife, who had shown us to our table and recommended a crisp local white, now stood at the front desk taking the evening’s reservations.

“A delicious lunch,” I said. (Grilled white asparagus, hake, and baby clams in an admirably flavorful broth, walnut cake for Ezra’s dessert, strawberries for me.)

“I like your hat,” she smiled her plaisir des sens smile back at me.

The straw brim having curled this way and that in transit, I didn’t believe her, but I wanted to and drew closer. Flyers and postcards advertising local products and art galleries were arranged beside her computer.

In bold Gothic font, walnut-brown, on a mustard-yellow background La Reine des Noix proclaimed its cornucopia: walnut halves, plain, caramelized, or chocolate covered; toasted, salted, with paprika, curry, or herbs de Provence; walnut oil; walnut butter; walnut syrup, walnut flour; walnut biscuits, meringues, and macaroons; cookies, buttery or crisp, gluten-free and/or artificially sweetened; walnut paste, sweet or savory with mustard; walnut tapenade to spread on walnut toasts

“May I take this?” I asked, forgetting the promise I’d made—no quests, no oversized longing. I felt like I’d found a shortcut to Oz.

“But of course… It’s not far from here. You would find it very interesting,” the wife grinned like she was sharing a secret, which I, under my broad-brimmed hat, had the savior faire to understand. “Tell Aurore Sylvie sent you.” She scrawled her name on the flyer.

“Look.” Returning to the table, I flourished the pamphlet at Ezra with my own saucy smile.

“I’ll drive.” He finished his espresso in one gulp and grabbed my hand.

Within minutes we had driven away from the bastide that rose clifflike off the valley floor and were climbing steep limestone hills through smaller and smaller hamlets, fields, and woods until the river, kayaks, pleasure barges, even the heartiest of mountain bikers were only dots in our imagination.

Ezra drove like a kid behind the wheel of a bumper car. He’d been cooped up too long. He’d always relished the chase. If he got lost driving from Montelimar to Maussane-les-Alpilles searching for an olive press open only on Wednesdays, a good lunch afterwards made for the perfect day.

Turn left, turn right, now right, the GPS instructed until she faded into oblivion. Ezra kept on, turning left, then right, then right again, as though he knew where we were headed.

“Where are we?” I asked, trying to imitate Sylvie, amused and self-assured.

“Uh…not sure.”

I took a deep breath. Maybe it was the wine; maybe the red umbrella, the spell cast by Sylvie’s smile, or the boundless offerings on the yellow brochure; maybe the tingle I felt when Ezra took my hand, but as much as I hated being lost, I couldn’t abandon my quest. I had placed my faith in La Reine des Noix.

Eyes scrunched, shoulder and elbow pressed right against the armrest, veering left across the gear shank as Ezra took the curves, I tried to read the map I had insisted on buying at the local presse for old times’ sake.

“Don’t need that anymore,” Ezra had teased, and I would have felt smug except we were beyond even Michelin’s reach. No grazing cows, no neatly variegated hectares of crops, the trees and grasses had turned scrubby and wild as we drove along a narrow ridge. Nothing about the landscape seemed familiar or French.

“Look at that view,” Ezra loved heights when in control behind the wheel.

“I can’t.” My eyes were fixed on the map, which when opened was longer than my arm span. Its length stretched from my lap to the roof. The air conditioner fan blew the map into my face, plastering my breasts. I tried to fold it in half and then in quarters, but the paper kept crumpling.

“Ezra,” I whined and scolded at once, “stop. I need to figure out where we are.”

“Too dangerous.”

I clutched the armrest as if it could steer us in the right direction. “Slow down. I’ll miss the signposts.”

“Signposts?” He scoffed.

“We’re lost,” I wailed.

“What do you want me to do?”

“This is serious,” I said. I wanted to find La Reine des Noix so badly nothing else mattered. I felt the way you do in a dream when you can’t find what you’re looking for. Dreading you won’t find it, you keep on dreaming.

“There,” I screeched. A tattered yellow paper sign was tacked to a tree; a hand-drawn arrow pointed down a gutted tractor path, “La Reine des Noix. Ezra, turn right, La Reine des Noix!”

“This is it?”

“Must be,” I pointed to another weathered yellow sign hanging from the top rung of a split rail fence that opened into a barnyard. La Reine des Noix was nothing like I had expected. Sliding from the SUV’s perch, I hit a puddle and made my way around clumps of wet dirt. No chickens clucked in the yard. No dogs ran out barking to warn us off. No walnut trees offered shade. What I’d imagined, a rural chic farm with lush trees and a glass solarium showroom, now seemed silly and beside the point.

“Let’s take a look around,” I acted as though there was nothing strange about the desolate, isolated farm.

“Hello, hello, bonjour,” Ezra cried.

We waited. Ezra walked up and down the yard. I stood as still as possible, willing someone to find us.

“Bonjour,” Ezra called more loudly, and this time a young woman approached us from the barn. Young woman, girl, I couldn’t decide. Her skin was white and smooth, opalescent, as though she had never seen the sun. Her face was large, her smile sweet if fixed. Her eyes reached up toward her forehead. Her body was round and firm like a new baby doll.

Down syndrome? I tried to place her. In fact, she was not like anyone I had ever met. Her floor-length blue-checked dress was spotless, her carriage proud, and when she offered her hand, I saw that her nails were perfectly shaped ovals.

“Welcome,” she spoke precisely, as if she wanted to make sure I understood.

“Is this La Reine des Noix?” I stammered in my best French, as flustered as she was dignified.

“But of course.”

“Is Aurore here?”

“Aurore? There is no Aurore here.”

“Sylvie sent me,” I asserted. Where were my manners?

“I know no Sylvie.” The girl was polite but firm.

Damn you, Sylvie, I muttered inwardly. “And you are?” I asked.

“I am the Walnut Queen,” the girl answered with a regal nod, which made an upside-down kind of sense. Magic potions should only be found in uncanny places.

“My pleasure.” I struggled to regain my composure though I was no match for the Queen, and continued to ramble “…the lunch, Le Plaisir des Sens, Sylvie. My husband,” I turned to Ezra.

“Monsieur,” the Queen extended her hand as if she expected Ezra to kiss it.

He took her hand, but his eyes kept darting around the barnyard.

“If it’s not too much trouble,” I asked, “we hoped to see your farm, purchase some products.”

“My pleasure.” The Queen guided us toward the barn, past a large tank-like cylindrical machine, which emitted whirring, grinding noises (for the walnuts, I supposed, though none were in sight), through a small screen door, and into a rabbit warren of rooms where two other women were working.

Both wore blue-checked dresses that fell to their ankles, identical to the Queen’s, and ruffled white aprons. They shared the Queen’s otherworldly pallor.

The Queen didn’t introduce us, nor did the other women stop their work to greet us. One woman, who might have been the Queen’s older sister or maiden aunt, went on stirring the contents of a huge copper vat, the kind people turn into planters and fill with geraniums, while a young beauty with braids like Rapunzel’s laid out oversized trays.

“I must help,” the Queen addressed us, “but please have a look.” She pointed to shelves where the tapenades, cookies, oils, and nougats stood labeled and priced and then joined the other women.

They worked deliberately and swiftly spooning a thick caramel-colored mixture from the vat into even rows on the trays in a silence so complete that I didn’t dare whisper. I stood transfixed, wanting to join in. Their competence and grace touched something deep inside me. It was like my grandma teaching me to bake, the alchemy of sifting and stirring flour, sugar, and eggs into a golden creation.

I’d nearly forgotten about Ezra until I heard a rumble in his throat like a low-running motor and turned to see him still standing by the door as though wary of coming farther into the Queen’s domain.

If he meant to signal he wanted to leave, I wasn’t ready. “Come over and help me pick.” I walked to the shelves.

He didn’t budge except to fold his arms across his chest.

What’s the matter with you? I wanted to say. Don’t I stand by while you chat up walnut sellers in the markets? Don’t I dress salad with walnut oil because you believe in its healing power? I’ve found you La Reine des Noix. What gives?

He glared back at me and shifted back and forth on his toes.

We can’t leave empty-handed. Give me a minute. Go wait outside. I pointed to the Queen in a clumsy charade and turned toward her wares.

From across the room, like a well-aimed dart, I felt something, Ezra’s fear or anger, I didn’t truly know what, pierce my back, and I began pulling things off the shelves as fast as I could. “I’m ready,” I told the Queen when the counter could hold no more.

She was as painstakingly slow at checkout as she had been swift at the tray. She wrote out each item, checked each price, added the total on an abacus, and checked again before handing me the receipt. The air was stifling. The windows were shuttered against the late afternoon heat, trapping the sweet caramel smell inside. I could only move in slow motion as I took out my wallet to pay.

“Enough,” Ezra shouted. “Don’t buy anything,” and he bolted outside, banging the screen door behind him.

“I’m so sorry,” I said. Shoving my wallet back in my bag, I turned away empty-handed.

“Ezra, I’m coming,” I called. Fear pulsed from my chest through my fingers and toes.

“Madame,” the Walnut Queen, who had followed me out the door, put her hand on my arm and handed me a paper bag. “These will help,” she promised.

I felt the bumps and chinks of shelled walnuts through the paper, so fresh they smelled sweet. I had no time to absorb their balm. I was afraid Ezra would snatch them and throw them away, so I stuffed the bag into my backpack before he could see.

The Queen returned inside while I trotted toward my husband glowering by the car. “Let’s get out of here.”

“Get in,” I ordered, “I’m driving.”

I turned out of the gate and onto the tractor path, but as soon as I reached the road, I didn’t remember which way to turn. Guessing blindly, I turned left, figuring I would see how to get home once we reached the valley floor, but the lane kept twisting. Every time I thought I was heading downhill, the road swerved up. There were no signs pointing toward towns I recognized, Souillac or Sarlat, no signs at all except tattered yellow posters reading “La Reine des Noix.”

The signs that had been sorely missing on our way to the farm were pulling me back to the Walnut Queen. I had to hold tight to fight the urge to turn back. The Queen was calling, I have more to teach you. I wanted her wisdom, but Ezra was miserable and frightened, huddled in his corner as far away from me as he could get. I needed to get him home as soon as I could.

After I don’t know how long we reached Gourdon, a gray medieval pile of a town, which stood off the valley floor like a giant gargoyle sticking off a cathedral.

“Should we stop?” I suggested, “Take a break?”

“No,” Ezra shuddered. He was pale and shaken.

I needed water and to collect my wits, but I was afraid if I stopped we’d never get home. The GPS was silent. I slowed down trying to extricate with one hand the map squashed under Ezra’s feet.

“Don’t stop,” he pleaded.

What was happening? I had never seen Ezra scared like this, not even when the oncologist told us his diagnosis.

I still didn’t know how to get home. I circled the ring road around the city once, twice, three times, looking for a directional sign to any town that I knew. Finally, a sign directed me toward Sarlat, thirty or forty kilometers out of the way, but I knew the route back to the barn from there. There were roundabouts to navigate with look-alike supermarkets and gas stations. Had I missed the turnoff? Had I passed that Carrefour before, or was it a Monoprix? My head and my back hurt. It must have been another half hour before I found the D704, a straight shot into Sarlat.

As we got close to home, Ezra sat upright and rubbed his eyes. I knew it was best to say nothing. When we reached the river road that led to the barn, I couldn’t wait any longer.

“Ezra,” I asked, “What happened back there?”

“You tell me,” he shot back.

“It was strange,” I said.

“Strange! What about the screams and moans?”

“Screams, moans?”

“Coming from that tank. Those women were witches, poisoning people and throwing them in the tank.”

In our forty years of marriage I had never felt so far away from Ezra.

“Good witches,” I insisted. How could Ezra be so blind to the Queen’s gifts? “She can help us.” I needed to convince him.

“How can she help us?”

“With the walnuts.” I patiently explained, recalling how warm and alive the nuts had felt, how gentle but firm the Queen’s hand on my arm.

“What?” he spat out. “You think walnuts can cure cancer?”

“Ezra,” I reminded him gently, “you’ve been buying walnuts all over the Périgord.”

The look that he gave me was so full of pity that I quivered.

“That,” he said, “was a joke.”

“A joke. Ha, ha, very funny. And the screams and the poison, also a joke?”

“Poetic license,” he said.

Ezra taught law. “Since when do you make use of poetic license?” I asked.

“You do and I had to get you out of there.”

I felt sore and sad and jumbled. “I didn’t mean…”

“No.” He was vehement. “I had to get you out of there. I saw that look in your eyes. Like when we were in India and the guide took us to that Hindu temple. I was scared you would never leave.”

I stayed awake until the storm passed trying to parse things out, though I didn’t understand much. When the storm ended, I wrapped my robe around me and went to the window. The wind had scattered the lawn chairs and the tree was still standing.

Annette Leavy is a psychotherapist and a writer of fiction and creative non-fiction living in Philadelphia, PA. Her work has been published in Caveat Lector and The Blue Lake Review.