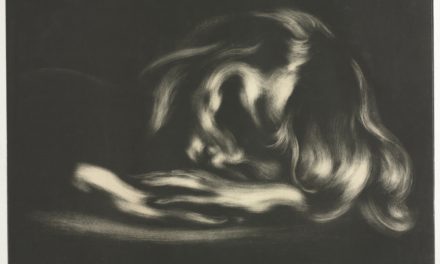

Vijf jachthonden, Wenceslaus Hollar, 1647. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

That Dog

by Susan V. Meyers

“Karen? Where are you?” She’d called him, frantic, in the middle of a workday—but now there was no answer. Matthew pressed harder against the front door, which was unlocked, but stuck. Behind it, there was a smell: a heavy, suffocating dog smell. Sandy, he thought. The old dog was big and cumbersome and often lost her balance. A big man, but one not used to using his body aggressively, Matthew pressed his full weight into the door, and the odor rose. A few inches more, and he could see the problem clearly: Sandy, her neck twisted too far to the left and her head smacked against the floor, was dead. The Jamesons’ house was split-level, the entryway crossed with two sets of stairs: one up and one down. Plenty of times, Matthew had advised his wife to keep the dog in her downstairs studio. Heavy, arthritic and half-blind, Sandy wasn’t able to manage most things by herself anymore: standing up, walking, relieving herself. And although Karen had the strong hands of a masseuse, the rest of her was small and slight. Undoubtedly, he thought, she had been trying to ease the dog down the stairs when Sandy slipped and fell. One more big heave, and the body slid against the floor, folding in on itself between the door and wall. “Karen?” his voice rang shrill against the emptiness. “Are you still in here?” He squeezed inside, careful not to step on the dog’s body or the pool of urine that it had leaked onto the floor. Upstairs in the bedroom, Karen lay face down on their bed, the sheets tangled and snot-streaked. He sat beside her, touching her lightly; she flinched. Her hands, worrying themselves, twitched at her sides. He knew it was a stupid question, but he asked anyway: “Baby, are you okay?” Karen’s head twisted up from the sweaty sheets, her eyes—red-rimmed and dilated wide like night vision—clicked in his direction. He took up a bundle of anxious fingers and held them in his own hands. “Shhh… C’mon, honey, try to relax.” Her hands tensed and pulsed. “Close your eyes,” he told her over and over—until finally she did. Then, he lifted a hand to push the hair out of her eyes. “Ok, that’s good. Breathe deep.” Karen’s face creased with concentration, but she did what he asked, taking one long, constricted breath. *** “Helene?” Matthew’s mother-in-law was not his favorite person, but she lived nearby, still drove, and generally had nothing to do. “Who’s this?” “It’s Matthew. Listen, Karen’s having problems today. I have to go out, and I don’t want to leave her here alone.” “What kind of problems?” Helene’s voice was thick; she coughed dryly. She’d been smoking again. “You know,” he answered, “what kind of problems.” His mother-in-law let the line go dead for a moment. “I thought we were through with all of that.” “Well, it’s a relapse or something. Her doctor said that might happen. Remember?” But Helene did not remember—or did not care to. “What did you do to her?” “Jesus, Helene,” Matthew glanced up quickly at the clock. It was just after one; the boys would be out of school by three. “I didn’t do anything. The dog died; she’s upset.” Helene didn’t say another word. She coughed. “Look, I’ve gotta take the body over to the vet—and pick up the boys from school. Can you please come over here?” “Yeah,” she sighed, her fingers working audibly on the lighter. “There’s nothing much going on over here.” Then she took a long, deliberate drag of her cigarette and exhaled into the phone. “I just don’t know what she saw in that old mutt.” *** Their boys were not upset about Sandy’s death. In truth, no one had enjoyed the dog’s company—not even Karen. The family had inherited the old dog from Karen’s father shortly before he’d died. By then, Sandy had already become a liability. Lethargic and sad, a stench followed her everywhere. It was okay, Matthew told his sons, to feel relieved. He was relieved, too. Sandy was old; it was time for her to go. “But Mommy,” he warned, “is pretty sad. Sandy was her dad’s dog, from before he died.” “Does she miss Grandpa?” Jay, the six-year-old, was always full of questions. “Yes, I think so. Anyway, it makes her sad. So, we’ve all got to be on our best behavior, all right?” Thomas and Jay watched closely. “Don’t worry, Dad,” Thomas answered finally. Nearly ten, he was already learning the value of diplomacy. “We’ll be good.” *** When they got back, Karen was awake. By then, she and her mother were sitting tersely in the living room. Helene looked up first: “How was the drive?” A cough drop clicked against her teeth. “Not too bad,” Matthew answered, and the boys studied their mother curiously as he shoved them off toward their rooms. “How are things here on the home front?” Bending down over his wife, he gave her a quick little kiss on the forehead. She didn’t respond. “My daughter was just wondering what you did with that old dog of hers.” Karen’s expression was tense and pallid. “Honey, I took Sandy over to Dr. Stevens. I had to.” She stiffened. “You didn’t ask me.” “Karen, she was a big old dog. We couldn’t bury her. That wouldn’t have been feasible.” His wife’s eyes flicked towards him. “But you didn’t even ask.” Matthew’s fingers slipped gently across her shoulders. “You weren’t calm enough to make a decision this morning,” he reminded her. “Listen, it’s better this way. Don’t you think so, Helene?” “Don’t look at me. I don’t even know why it’s worth arguing about.” She unwrapped another cough drop. “Henry wouldn’t have minded, you know, Karen, if you’d put that dog down months ago. If your father was anything, he was practical.” Karen turned. “He would have minded,” she spat. “And what would you know about it? He only got that dog because he was so lonely after you left him.” Her fingers, shoved beneath her thighs, gripped the seat cushion. Matthew watched her carefully. Those attacks she used to have—the tense breathing, the dilated eyes, the panic—they had usually come on at moments like these. But Helene remained cool. She popped the fresh cough drop into her mouth and worked it evenly along one cheek. Nearing sixty, she was still an attractive woman: slender and slow-limbed and neatly dressed. “If he was so goddamned lonely, he shouldn’t have run me off.” Karen, her voice too loud now that the boys are home, yanked her hands free and slapped them against the armrests of her chair: “Goddamn it, Mom, why don’t you just go home?” “Because your fine husband here asked me to come keep an eye on you, in case you got hysterical again.” “I’m not hysterical.” Karen eyed them both. Helene sucked her lozenge, turning it over back and forth in her mouth. “All right. I guess I’ll go, then. See you later, Matty.” *** The following evening, there were two messages on the answering machine from Helene. One had been left at noon—Karen had been downstairs giving a massage—but the second was from six o’clock, just before Matthew had gotten home from work. Karen stood at the kitchen stove heating a pot of soup for dinner. “Your mom called. Why didn’t you pick up?” “I don’t want to talk to her.” Carefully, she dipped the pad of her finger into the warming soup and lifted it to her mouth for a taste. She added more salt. “She’s just checking on you.” Karen turned and grabbed a clinking pile of ceramic bowls out of the cabinet. “I don’t want to deal with it right now.” Matthew had little idea what Karen’s relationship with her mother had been like in childhood. But for the past two decades, since Helene had left her sullen husband, the two women had been at odds. Helene claimed that she had only left once Henry had begun leaving bruises on their daughter. But Karen swore her father never touched her. He was a stern, gruff man, but he loved her. She left it at that. Even three years into their marriage, when the old man was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, they had rarely talked about him. Because he was sick, Karen had moved him into assisted living a few miles from their home. And that was when they had taken the dog, Sandy. For the two subsequent years of his decline, Karen had visited her father with resolute consistency, checking his supplies of magazines and medicines, or his favorite flavor of sherbet in the community fridge. Matthew didn’t join her very often, but during his few brief encounters with the man, he had learned all that he thought he needed to know. Whenever Karen left the two of them alone, the old man had begged Matthew for a drink, his withered hands gripping violently at blankets or armrests. A fury of recognition lit his eyes each time: He didn’t know who Matthew was, but he was a man—so he should understand. *** It is Jay’s idea to get another dog. To a six-year-old, the solution was logical: His mother was sad because the dog died; get another dog, and she wouldn’t be sad. The notion was overly simplistic, of course, but Matthew’s patience was waning. Two weeks after Sandy’s death, Karen continued skulking about—struck by some kind of prolonged grief that, he thought, should have worn itself out a long time ago. Something needed to be done. So, he’d agreed to Jay’s impractical plan, and he and the boys had funneled into the family car. At the pet shop, Thomas and Jay flushed distracted by the long, colorful tanks of fish, turtles, and lizards; the square, wire frame cubes full of parakeets and cockatoos; and stranger beasts like glassed-in snakes and tarantulas. Matthew let them explore the mysterious aisles, black-lit aquariums, and odd-smelling pet foods, while he surveyed the puppies. There were nearly a dozen dogs: a handful in a cage marked “Small Dog,” and the rest in the “Large Dog” cage. A large dog seemed appropriate, though he didn’t want a puppy that looked like Sandy. No cocker spaniels, no German Shepherds. What they needed, he decided, was a sleek, healthy-looking animal. Like the little black Labrador, $250, in the bottom cage. “Hey boys!” he called. “Thomas! Jay!” His sons emerged, carrying a rhinestone-studded dog collar and a rubber squeak toy. “Can we get these for the dog?” Thomas asked, while Jay beamed, nearly sweating from the excitement of the place. “Sure, guys, but first we’re gonna need the dog, right?” They looked at each other, nodding slowly. “How do you like this one?” Matthew slid his finger into the wire mesh close to the black lab. The puppy gave a high, endearing bark and batted at the finger. Jay laughed. Thomas tried it, too, his finger squirming at the nuzzle of a moist, black nose. “All right,” he agreed, handing his father the collar and the rubber squeak toy. *** His first mistake buying that dog, Matthew realized later, was to make it a surprise. The second mistake was assuming that the dog would be an easy addition to their lives: a lively, cheerful presence. A plaything. But during the puppy’s first few excited minutes in its new home, it squealed, snapped aggressively at their fingers, and peed not once but twice on the carpet. The boys, squealing with excitement, chased it through the upstairs rooms. “Hey—hey guys,” Matthew cornered them in the kitchen, where they sat watching the puppy sniff out crumbs in the corners. “Shhh, c’mon guys. Mommy’s trying to rest, remember?” “What’s its name?” Jay asked. The puppy nosed something by the oven and gave a high-pitched sneeze, sending the boys into riots of laughter. “Jay! Jay! I said be quiet. I need to go to the store for dog food, all right? You need to be good here for a few minutes by yourselves.” Jay gulped a breath of air and covered his mouth with both hands, wide-eyed and grinning. He nodded. Thomas looked over at his brother and told him matter-of-factly: “It doesn’t have a name because we haven’t named it yet.” An hour later, by the time Matthew got back from the store, Karen stood barefoot at the top of the stairs holding her soiled socks up in the air, out and away from her body. “This dog,” she said flatly, “is the devil. Where on earth did you get it?” Matthew sighed, shifting the weight of the grocery bags against his torso. “The pet store,” he admitted quietly. She looked down alarmed at the heft of paper towels and dog chow in his hands. “I’ve got pee on my socks.” “I know. I’m sorry. I’ll clean it up. Just calm down.” “I am calm,” she answered, eyeing him from the height of the stairs, and turned back toward the bedroom. *** Helene was likewise chagrined by the family’s spontaneous solution to Karen’s grief. “What the hell’d you do that for?” she barked accusingly over the phone. “It’s like medicine,” Matthew explained. “Haven’t you ever heard of getting a new pet to replace one that died?” “One fleabag for another? Doesn’t sound so hot to me. And Karen hates dogs. Always has.” “That’s not true, Helene. She got really attached to Sandy once we had her. But it doesn’t really matter. We’ve got the dog now.” “It most certainly does matter. Karen’s not well.” “Helene,” he gritted his teeth, “the boys love it. And Karen will come around. It’ll be good for her.” “Don’t be so sure you know everything about her, Matty. I’ve known Karen a hell of a lot longer than you have.” “Well,” he snapped, “at least she’s still willing to talk to me.” There was a sharp intake of breath, and Helene hung up the phone. *** Even so, he realized that his mother-in-law was right. After more than a month with the dog, Karen remained sullen, and her sleep was failing; many nights she woke with nightmares. For their part, the boys’ concerted interest in the new puppy lasted for about a week—enough time for them to take up their mother’s sarcasm as a name for the dog: Lucifer. “It’s cool,” Thomas had announced shortly, and Jay nodded. But after that initial week, puppy charm wore thin as Lucifer began finding chewable items among their toys: Legos, Nerf footballs, plastic action heroes. The day the puppy gleefully dragged a deranged Pokemon figurine out into the living room, Jay cried and swore he hated the dog. Then the boys had gone back to their old amusements, and the puppy sulked in a corner chewing at a rawhide bone—or nosed his way into the kitchen, wetting the floor out of spite. “Why don’t you guys play with Lucifer?” Matthew asked. “Mom said we could play video games,” Thomas answered without looking up. “And the dog can’t play with you?” Thomas turned away from the screen for a moment to give his father serious study: “No.” The only person who seemed to care for the dog was a neighbor boy, Nathan Sheridan, who had begun visiting their house daily. Seven years old, Nathan was just old enough to earn Jay’s respect and just young enough for nine-year-old Thomas to boss around. He had always been one of the boys’ playmates, but now he came over primarily to visit Lucifer—and the puppy relished the attention. Twice, Nathan had innocently allowed Lucifer to follow him the four blocks back to his house, where his mother, embarrassed, had discovered the error and promptly returned the dog. Then Matthew had had to pin Lucifer, barking, inside the house while Nathan and his mother had disappeared again down the street. The solution, he thought, was clear enough. Nathan loved Lucifer. He had never had a pet before because his father was allergic. But the Sheridans had been divorced for over a year now, and Nathan’s father had moved out of state. “But what about Karen? What does she think?” Marissa Sheridan asked when he went over to offer them the dog. The two women were nearly the same age; and, although they didn’t know each other well, they were friendly, having shared coffee two or three times. When Marisa’s husband left, Karen had brought over fresh casseroles every day for a week. “Karen will be happier without Lucifer. It’s too much for her having an active puppy around.” “But are you sure? I mean, Nathan just loves that dog, but it’s your dog. Have you talked with Karen about it?” “Trust me; this is what’s best. Karen’s tired. I just need to take care of things right now.” *** It took two full days for Karen to realize that the dog was gone. “Matthew,” she asked one evening after the boys were in bed, “where’s that dog?” “You didn’t want it, so I got rid of it.” Karen fell silent. She looked tired. “Don’t worry, baby. The Sheridans really want Lucifer, and we don’t.” He reached out and took her hand. “You didn’t ask me.” Her voice was stiff. “No,” he answered. “But you haven’t been well lately. Somebody’s got to keep things going around here.” At two-thirty that morning, Karen woke up screaming. Matthew tried to calm her, but she was delirious—shaking and choking against her breath. “You never liked him,” she gasped, trying to wiggle herself free of his arms. “You always hated him.” He held on. “You hated him! hated him!” “Shhhh!” he shook her, hard. The boys’ rooms were just down the hall, within earshot. “Karen, shhh… stop it.” “You hated him. But he never, he never.” Her eyes fell shut. She went limp. “He never…” Nothing about Karen’s father had been easy; he was a rough, terse old man. And she was right, Matthew thought: he had never liked the man. When the stroke came, it had seemed like a blessing—that, and the nurse’s careful but firm suggestion: let him go. He and Karen had been the ones to decide. The answer, he’d thought, had been so clear. For nearly two years, Karen been caring for her father—worrying over him. And by then, she was pregnant again. It didn’t matter that he wouldn’t see the new baby, Matthew had assured her. He wouldn’t understand. By then, he’d hardly recognized Karen. When she finally quieted down, he held her the rest of the night. Giving his wife comfort: this was something that made Matthew feel useful. In the morning, he left her sleeping. *** That day’s urgent phone call came not from his wife but the county hospital. There had been an accident. Physically, he was assured, his wife was fine, but they were holding her for a few days in the psychiatric ward. “My god,” he breathed into the line and made the woman explain it to him again. “Sir,” the nurse answered. “I don’t have the full report in front of me. You’ll have to talk with the caseworker.” But once he got the police report, it was easy enough to imagine what had happened that morning. Karen had been alone; no massage patients until noon. Marissa Sheridan was at work, and Nathan was certainly at school. Karen had known what she was doing when she went over to their house. She’d known that Marissa never put a lock on the backyard fence. And she’d known that Lucifer would be there. What she hadn’t known, he supposed, was how much Lucifer resented her; he’d probably begun barking even before she’d opened the gate. Maybe she’d brought food to lure him. Certainly she’d had a leash; the police had taken it from her hands when they’d found her. But it wasn’t hard to imagine how, upon finding the gate open and Karen in the yard, Lucifer had run—and Karen had chased yelling after him. The quarter mile between their street and Bridger Way, the closest arterial road, was uphill. So, he thought, it was possible that Karen was already light-headed by the time she’d caught up with Lucifer, who had run out into the middle of the road. Her calls, Here Lucifer!, must have aggravated him; he’d leaped toward the opposite shoulder, and been hit. Karen, the driver had explained, had screamed so shrilly that he thought he’d killed a person. She’d collapsed on the side of the road, crying and heaving, while he’d stopped the car: “Lady, lady, I’m sorry. Your dog just ran right out in fronta me. I couldn’t stop.” But Karen had been unintelligible; she’d scared him. Within minutes, police had arrived, as well as an ambulance that had rushed his wife to the hospital. “She doesn’t want visitors.” Ms. Jenkins, the hospital social worker, was a crisp, silver-haired woman in her late forties. She was gentle but unflinching. “But I’m her husband.” “Mr. Hardwick,” the woman answered, tucking her metal clipboard against her narrow chest. “Sometimes a person just needs a break.” He watched her neat frame fill the hallway in front of him. What she suggested was unbelievable. “But what about our kids?” he slapped a hand against the concrete wall; the sound echoed flatly, and stopped. “What am I supposed to tell them?” The woman’s head bobbed lightly. “Your wife will be fine,” she said simply. “Tell your children that. The truth’s not such a terrible thing.” *** “When’s she coming home?” Jay wanted to know. “When she feels better.” “But when is that?” Jay started sucking his thumb nervously. Matthew eased it out of his mouth and held his hand. “When the doctors are done helping her.” “Mommy’s sad.” Jay lowered his eyes and moved his body closer toward his dad. “That’s dumb,” Thomas retorted. “Nobody gets that sad about an old dog. Our mother’s fine.” Helene was less easy to convince. When Matthew explained the details of what had happened, she remained uncharacteristically silent for a moment. “She’s in the hospital?” “Yes.” “In the mental ward?” “They’re social workers,” he clarified. “They deal with people’s break-downs all the time.” “And what do they say?” “She needs a break, but the therapist there said Karen will be okay. It’s not a permanent psychosis.” Helene remained quiet for another minute. Her breath was heavy. Matthew listened hard, trying to decide whether or not she was crying. “Well shit,” she said finally. “What?” “You heard me. Shit—I was hoping this wouldn’t happen.” “What wouldn’t happen?” “This. Karen ending up so bad off from all that grief. She doesn’t deserve it. And I know you think I never did anything to stop it, but I did what I could. I got her away from her father, and then I let her think what she wanted to about the man. She chose to forget all the shit he did to us, and I let her. If that’s not motherly protection, I don’t know what is.” She turned away from the phone to cough. Matthew heard ice clinking in a glass. She swallowed. “Well, it’s your turn now, Matthew. You take good care of my girl.” *** The following morning, Helene pulled into their drive at eight a.m. “You’re not going to work today, Matty,” she said, gathering the boys’ backpacks, checking for books, pencils, paper. “You call in sick, and I’ll take care of the boys.” Helene hated hospitals; Matthew knew this. But, he should be there, she knew—even with nothing to do. Even with the worry aching inside him and nothing to distract it. This is it. The thought was growing unshakeable: Our marriage is ending. Although how things had come so far, he didn’t quite understand. When he arrived, however, Ms. Jenkins reported that Karen was doing better; she had become somewhat intelligible. “She’s been pretty confused,” the woman admitted, holding out a cup of black coffee. “Poor girl hasn’t been able to tell a straight story since she got here: who fell down the stairs, who had the stroke, who ran out in front of the car.” Matthew listened, grimacing: His wife was turning crazy. “But today has been better,” she chirped. “She’s much more lucid, and she’s told me a lot about her father. What a handful.” Matthew cleared his throat. “Yes, from what I’ve heard.” Ms. Jenkins put a hand on his arm. “Matthew, your wife’s going be all right. She’s a strong woman.” In the hospital bed, though, Karen looked tiny, helpless. Her skin tone was off, but her eyes were clear. She smiled as he walked in. “I know I look like hell.” “No, no,” he lied, falling into the chair beside her bed. She was a gaunt figure, diluted like watercolor, but still beautiful. God, he thought, how he had missed her. “It’s been quite a few weeks,” she breathed. Her skin was so pale that he could see the thin purple veins at her temple and throat. Leaning toward her, he slid her face between his hands, pressing palms against cheeks; he wanted so badly to protect her. “They say I’ll be fine,” she continued lithely, taking up one of his hands in hers. “What do you think?” “I think you’re talking to me, and that’s an improvement.” She smiled gently and began massaging the muscles in his hand. “You’re tense.” “Yeah,” his voice rattled, “things haven’t been so easy lately.” “I know.” They remained quiet for another moment. Then she laughed, “Goddamit, I know,” and pressed his hand between hers to warm the muscles. The real work of massage, Karen had often told her husband, isn’t movement, but touch. “God, what an awful couple of months,” she shook her head. “How are the boys holding up? I feel like I haven’t seen them in weeks.” “They’re all right. Your mom’s staying over at the house—she’s been helpful.” Karen opened her hands and began fingering the muscles of his palm. “Good, good. We’ll have to do something, the four of us, when this is all over. A vacation or something. Even for a weekend. Whatever you and the boys want to do.” He nodded, his relief so great that he felt himself breaking into a light sweat. We’re okay, he breathed. We are going to be okay. Karen sat quietly, easing the pressure out of his hands, following the lines of his bones with her own strong fingers. And it was working. He felt himself relaxing, letting it all go. Everything he wanted right then, Matthew told himself, was what he had there with him: his frail but healthy wife, her hands, her beautiful touch. But then, like it meant nothing at all, Karen shattered the moment: “I killed him, Matthew.” She looked squarely up at him, pressing his hand between hers. “I killed him, you know?” “What?” Matthew felt his stomach lurch upward: a thick pen across paper; the slow stutter of machines; and all of his own sudden shame, melting like wax. He cleared his throat. “What do you mean?” “The dog.” Oh, that! he breathed, relieved. Why that was nothing at all! “No you didn’t, honey,” Matthew grinned in spite of himself, relieved as he was. “It wasn’t your fault,” he assured his wife. “It was an accident. Anybody could’ve…” “No,” she stopped him cold, her hands so firm on his own that he couldn’t have taken them back if he had tried. “I did. I killed that dog.” Susan V. Meyers has lived and taught in Chile, Costa Rica, and Mexico. She earned an MFA from the University of Minnesota and a PhD from the University of Arizona, and she currently directs the Creative Writing Program at Seattle University. Her fiction and nonfiction have been supported by grants from the Fulbright foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, 4Culture, Artist Trust, and the Squaw Valley Community of Writers, as well as several artists residencies. Her novel Failing the Trapeze won the Nilsen Award for a First Novel and the Fiction Attic Press Award for a First Novel, and it was a finalist for the New American Fiction Award. Other work has recently appeared in Per Contra, Calyx, Dogwood, The Portland Review, and The Minnesota Review, and it has twice been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.