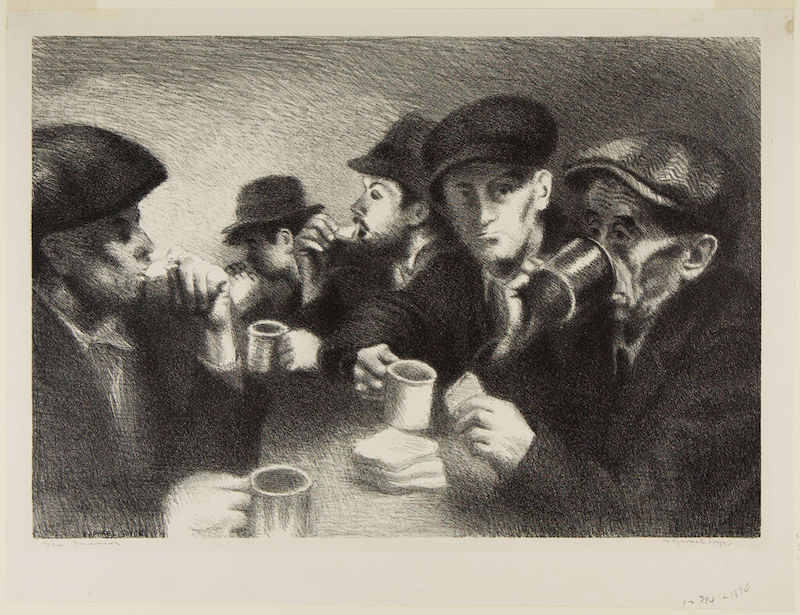

Soyer, Raphael. The Mission. Harvard Art Museums.

Shleppers

by Mark Mirsky

In the grey filter of light that my windows draw in from the dawn, a little man appears bowed over by the weight of the bag he is carrying as he shleps, drags himself and his burden from one corridor of offices and workshops to another. I am half-awake but it is no dream, though summoned from a dream or a corridor far away in my memories under the influence of an hour that is still subject to the night before.

I know the diminutive figure; though I saw him only once, fifty-three years ago on the upper floors of a massive building in the old Seventh Avenue Garment District below Forty-Second Street. He was practically a dwarf. Whether he had been born that small or his troubles, tsurris, had pressed him down into that shape, I couldn’t tell. Was he in his late seventies? A bad diet, tsurris, his, and that of several generations before him in Eastern Europe, might have explained his size, aged him prematurely. I don’t exactly remember his accent, but I believe it had the melodies of Yiddish in the few discouraged words he spoke.

I was only twenty-four and in the company of two brothers, guys from the Bronx in the days before the great flight from what was the barrio of Eastern European Jews. They were selling bolts of cloth from a small shop as you descended into one of Manhattan’s West Side subway entries. The brothers were obviously good hustlers, and the tiny man with the grey face and hunched shoulders was not. My eyes went to the little man’s bag, which was oversized, and seemed to be pulling him down into a sea of troubles. The brothers explained to me quickly, as they bandied a few words back and forth with the diminutive figure, that it was filled with samples of cloth that came from the leftovers of bolts that hadn’t been entirely used, bits of this and that. The little man was trying to peddle these remnants to tailoring firms who needed no more than a yard or two to fill out an order rather than buying in bulk.

The Garment District bosses, even at the multi-million dollar firms, whose smart suits and fashionable dress deals were international commodities, with the typical self-mockery of their Polish and Russian ancestors, referred to their business as shmutties. It was a word that I, and every other kid who grew up in a Jewish neighborhood in the 1940s, knew. A few words of Yiddish were so common that they filtered into our speech without our being aware of it. A shmutty was a rag, but the word carried dozens of associations.

The brothers, feigning curiosity, had asked the tiny man, stopped in the corridor by their hearty greeting to show us the contents of his bag. He complied, dropping its weight on the floor of the wide corridor under a high golden ceiling. The Garment Center’s sky, in this lobby, was lit by chandeliers, and the tiny man looked up at them with a flicker of hope on a face starched into permanent wrinkles. It was painfully obvious though I knew nothing of the shmutty business, that what was stuffed in there was probably un-saleable. What came out was colorful but the samples were limp, tattered at their edges, worn from being pulled out and pushed into a battered bag.

What my mother called shmutties were the remnants of shirts, bedspreads, hand or dishtowels that had ripped in our house. They were cut into rectangles to wipe a table, dust a bureau. After being rubbed toward oblivion the shmutty went through the wash but suffered a further indignity to blow a nose in, or be dabbed in a bottle of furniture polish. Only when judged without any possible use, did it go into the garbage. Until then it resided in my mother’s ragbag. The dwarf’s bulging valise brought her sack to mind.

The clucking enthusiasm of the two brothers standing with me over this hapless salesman half their size was painful. “It looks good—no question! How much do you have of it?” or “These? You won’t have any trouble finding a buyer for,” as the bent figure drew one remnant after another out for inspection, “Oh, yes,” and “That—you watch, someone is going to grab.”

After we broke off and moved away, they smiled mischievously but not without a sigh of fellow feeling as if looking into the future down the brightly lit corridor at what might lie ahead for us all—a distant moment when luck and judgment had fled and reduced us to shleppers. Their shrug spoke what even they, who savored every other word of speed as a joke, did not want to say out loud. Hopeless.

I had come to New York City that year to be an actor. I had a single tryout for a Broadway show to which I was sent by a young agent, a woman glowing with health and enthusiasm, not many years older than me. I went in for the audition thinking I should play it as a method actor where one did not perform; one simply was oneself. The play was about Russian Communists and I could have produced with ease the sort of voice they were casting for. But I never got to read the script aloud. I was betrayed by my Boston accent.

They asked me my name, “Mah-k.”

“You have a broad accent!” they said in shock, freezing at the missing r.

“It goes away in the pah-t,” I snapped back, confounding the problem.

“The what?”

It dawned on me, what just happened, and I dropped my voice into its lower range, and slowly pronounced, “It goes away in the parrt,” growling out the r but the audition was over. My Equity card, my fairly long resume in summer stock, the fact that actors I had worked with were on their way to Hollywood—all of that was useless. My beautiful agent immediately dropped me. She had never seen me on a stage, just read my reviews, and heard the recommendation of others.

I began to think about another skill I had practiced with success at college—directing plays. It was attractive if only because I could avoid the humiliation of mass casting sessions. I had run into a talented actress whom I had studied with during a summer session at the Neighborhood Playhouse in New York City between my freshman and sophomore college year. At the Playhouse they taught the famous “method” of Stanislavsky, which had formed actors like Marlon Brando, as well as classes in movement and elocution, the fatal “method” which had convinced me to present myself rather than my skills as a character actor to the producers. I was very adept at accents and at will could sound like Lawrence Olivier in Shakespeare’s Richard the Third or John Gielgud in Hamlet. In school and on the professional stage, I had played any number of older men in the classical repertoire, kings, lawyers, demented veterans, many with deep European-inflected English.

The actress, hearing my tale of woe, asked if I was interested in work as a director. Yes, of course. I had almost gone off on a Fulbright to study directing in London right after college, and only a snafu at the State Department had sent me instead to the Creative Writing M.A. program at Stanford, with a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship. The actress, a gifted performer in the classes we both took at the Playhouse, was a friend of the administrator of a program in Manhattan that linked aspiring playwrights with professional actors and directors. There was no pay attached to the position but it was a way to get one’s foot in the door of the New York Theater and I was still stage struck.

I found myself with actors whom I found pompous and dreary (one went out to Hollywood and had a momentary career in the movies). The play was so dull the lines began to sound in my ears like chalk grating on a blackboard. What I did find of interest were two friends of the playwright, and a girlfriend who tagged along. They came to almost every rehearsal.

These were the two brothers from the Bronx.

The actors did not want to be told what to do, and the playwright had no interest in my suggestions. The brothers though recognized in me a lost cousin from another geography. At that first rehearsal they adopted me. While playwright and actors hurried away, the two brothers, who sat in the scattering of chairs at the back of the room where the rehearsal took place, clung to me. They had a young woman in tow, no more than twenty-one, and insisted that I go out with them for a cup of coffee. At the table in a place nearby we instantly felt our tribal affinities. Our laughs were tickled by common grandparents in the Pale of Settlement. An old sarcastic humor infused their fast-talking Bronx lilt and my broad Boston, at the back of both a careful ear could hear the music of the Talmud’s interrogative. Not that I was a scholar but my father was, my grandfather a better one, my great-grandfather a sage. Whether religious or secular, Orthodox or socialist, one inherited the same mocking rabbinic wit.

The older brother, a bachelor somewhere in his late thirties or early forties, was the shorter of the two. His black eyes had a bright light so intense it seemed reflected from the moon. He was the most sympathetic; his energy keeping him restless even at the Midtown diner where we sat. Back and forth he rustled against the back of the bench, ready to spring into the air over his rice pudding. The younger, no more than thirty, slightly taller than his brother, was slower, stolid, echoing his elder’s enthusiasms, with a dogged goodwill, but at his side was that dazzling young woman. Her body burst out of her tight dress with the shape of a Hollywood princess, but her face was a blank; naive, innocent? It retained the expression of an adolescent of thirteen or fourteen, at odds with her body, one of those inscrutable females who had held me hypnotized all through my painful teenage years. What attracted girls my age or younger to partners who weren’t handsome, didn’t have more than average intelligence? I had come from a self-enclosed world in Boston of eighty thousand Jews, their butcher shops, groceries, and candy stores, three or four restaurants (one of which kept kosher). The wealthier dentists and lawyers had already begun to move away to the affluent suburbs outside the city and assimilate. The Bronx at this moment still boasted over half a million Jews. Its buildings along the Grand Concourse housed its accountants, doctors, and shrewd businessmen. The Concourse still maintained its reputation for luxury. Even the ranks of salesmen in the lower echelons of trade like the brothers, buoyed by the boroughs weight of numbers, affected a swagger. The Jewish Bronx endowed its residents with a confidence, a chutzpah, which we in the smaller enclaves of Massachusetts were careful no matter how smart or talented to repress. And that Bronx aura lay over the shoulders of both brothers as if they were “in the know.”

When I came to Manhattan my father told me that as a result of my six months of active duty in the Air Force Medical Corps as a psychiatric ward attendant, I was entitled to unemployment insurance. It amounted to about eighteen dollars a week. My rent was only twenty-three dollars a month and the Polish restaurants in my Lower East Side neighborhood served a ninety-nine cent special; a plate with a chopped meat patty buried in mushrooms, mashed potatoes, carrots, a dish of coleslaw, and a rice pudding for desert. Between the box of dry spaghetti on my shelf in the two and a half rooms (the kitchen, a bathtub in it, was one of them) and glasses of tap water on the weekend I was able to survive through my first months in the city. I knew I was going to have to look for work though, since I was living from one tiny check to the other. The brothers, who lingered after every rehearsal clucked with sympathy as I talked about myself, discussed my options with them. They couldn’t employ me since their own business ran on a curtain string, but they invited me to tour the Fashion Industry buildings with them.

We went by their shop on the day I took them up on this offer. It was squeezed into an angle of a set of stairs that went down one level from the entry on a narrow cross street of breakfast and lunchtime joints, stores of discounted electronics, novelty items, bargains, just off the broad vista of Seventh—Fashion Avenue. Their shop was more of an interior stall built in the shallow triangle formed by the intersection of the back wall and sidewall at the bottom of the first level of stairs. A glass window had been erected at the broad front of the triangle and bolts of cloth were displayed behind it. When the shop was open, wooden stalls placed outside were filled with samples so that pedestrians coming down to take a subway could pause and finger the bolts sold inside. How this store, almost as sad and tiny as the little man I would meet, could support even one of the brothers, was a puzzle. I suspect that they juggled other employment to keep it running.

From the shop below the subway entry we climbed to the street again and hurried toward one of the multi-floored palaces of Seventh Avenue. They were going to show me where they acquired their bolts of cloth, among the bargains of the remnants to be garnered in the heart of the industry. The brothers were sure that with my Harvard Degree and my pending Masters of Arts, from Stanford, I would touch the heart of one of the fashion magnates who would find me a suitable position. In fact at the end of the day, they had arranged an interview for the next morning. Not a proposal for an actual job, but I was to learn the business, possibly help out at their shop as well. In short, I was to intern or become an apprentice.

I recall that I left with a sense of dread. The blinds were being drawn on a life that I had entertained great hopes about. I liked the brothers, their enthusiasm, their banter and how they turned their childhood in the Bronx ghetto and its claustrophobia, into the premise of their wit. The sheer number of survivors in Jewish New York had made real for me the darker nightmare that the Jewish world had undergone in Europe, the human scar of the Holocaust. Its victims were unashamed to show their tattoos, and those blue marks always registered. I patronized on the day after my week’s check arrived, a dairy on Second Avenue, so narrow there was just room for a single row of tables, one seat on either side, beyond the counter. It advertised over the counter that its vegetarian liver had: “the real Yiddesheh geshmack” but it tasted as well of the death camp’ tattoos, digits incised into the countermen’s arms, below the short sleeves of their white shirts. They showed the world that they were survivors. The Lower East Side dairy restaurants were also remnants of a dying Jewish world. You could taste it in the liver and at the bottom of the dairy’s cabbage soups, a dreadful sweetness.

The older brother seemed to have leapt out of pages of an American Sholom Aleichem, a merry luftmensch, living on hopes and dreams. He was desperate, I felt, to have my company with him in the air. His brother, as if ceding center stage to his garrulous brother, said little, which perhaps endeared him to his even quieter girlfriend, whom I suspected he had lifted from one of Fashion Avenue palaces’ display windows. As the three of us went on for hours talking and laughing at the tables after rehearsals, I doubt that I heard her say more than two or three words.

I imagined intriguing possibilities with this young woman, but though exotic she was as silent sitting beside the brothers as a mannequin. I was afraid that in the unlikely event that I could find my way under her well-cut clothes, all her curves would be plaster. Those girls I had been in love with as a boy of thirteen, fourteen, in Dorchester and Mattapan, girls who at twelve were already fully developed women, at thirteen modeling for the agencies in Boston and at fourteen dating baseball players from the Boston Red Sox were untouchable, also, unreadable. Under the immaculate makeup, the fashion-conscious clothes, despite the provocative movement of hips as they strutted down the steps of the two and three-floor brick apartment buildings that lined both sides of my street, I had no clue to what went on in their heads.

I can’t get those years out of my head when as “an unlick’d bear whelp,” a disappointment at school, a failure to my father, an awkward embarrassment to my glamorous mother, not seeming particularly bright or attractive to any of the girls I met at the house parties that the group of boys with whom I had formed a sort of social club, I wandered the main street of the Jewish district, Blue Hill Avenue. Somehow this silent girl seemed as if she was a prize waiting in the antechambers of the Fashion Industry, she or her likeness, a princess of the Bronx, if I consented to accompany the brothers.

Actor, director, or a rising star in shmutties, my life felt like a ragbag in those days—anything might turn up. I had hidden in books through adolescence, and the vocabulary, the sensibility I had acquired, as well as my skills as an actor, had catapulted me into two of America’s most prestigious colleges, but I felt as if I was falling back into the nightmares of my adolescence. One day due to the friends I had made at the college, I was due at the Rockefellers, invited to their estate at Tarrytown. In the brilliant light of Sunday morning that weekend I knocked golf balls between the oversized thighs of an enormous woman cast in bronze. A smaller bronze of the famous sculptor dominated the garden of the Museum of Modern Art back in Manhattan. A private green stretched before the front terrace of one of the family mansions.

A classmate was dating one of the banker David Rockefeller’s daughters, and after my futile game of golf, on that terrace the day before, while I continued to stare at the oversized hindquarters of that metal sculpture, my friend discussed a business scheme. The two of us would go into a business in lumber. We could buy the enormous logs that were to be found and felled in the forests of Peru and ship them to the United States. Cooled by the breeze from the Lordly Hudson nearby, under the protection of the larger-than-life bronze lady, it seemed a credible career, fertile with possibilities.

Monday morning, however, found me waiting in line at the Unemployment Insurance offices. There I had to plead that I had been looking unsuccessfully for work as an actor, and fend off suggestions that I settle for a job as a dishwasher or busboy.

As the warm sun of September, sponsor of these dreams, slowly sank toward the equator, tickling the roots of rain forests in Peru, it found me on the chilling sidewalks of New York City, still reporting to my weekly appointment in the long sober line of unhappy men and women. Like me, they were trying to get by on minuscule unemployment checks. The search for work, reality, asserted itself in the sour faces of the clerks. It was remarkable that whether male or female, their suspicious, unsympathetic expressions had been pickled to the same degree of tart taste and in the self-same jar of gherkins. As a card-carrying union member I hoped, suspected, that they could not force me onto the lowest rung of the city’s employees, sweeping restaurant floors or bagging groceries, but they snarled and exuded vinegar at the corners of their mouths when I refused.

My weeks of entitlement to unemployment insurance were coming to an end, however, and the funds in my bank account dwindling. Water and spaghetti weekends would soon extend into the weekdays. I was going to have to find a paying job. The brothers’ offer to find me something in the garment district no longer seemed a joke, but something I should take seriously.

#

As I shuffle back through images that remain intact in my memory, I know that I never went to the appointment I had at a business in the Garment District for a job. I never showed up again at the shop of the brothers, down a level in that subway entry. I was stopped by what took place on November 22, 1963. I was supposed to go to an address on Seventh Avenue the following Monday. John F. Kennedy was shot on Friday as that weekend began, followed by the shooting of his presumed assassin Lee Harvey Oswald at the hands of Jack Ruby. Followed by the grim, suspicious comedy of Ruby, a small-time stooge as the avenging sword of the Republic, the rapid fire of events made me and many others feel as if the United States was under attack. The national catastrophe stopped me in my tracks and the idea of jumping into the hoops of Seventh Avenue seemed impossible. My father had been an influential political figure in the Massachusetts legislature who knew Jack Kennedy in the flesh, his brother Bobby, in their rough and tumble ride to the top. Passing the newsstands and their screaming headlines, I sought out a television set where the footage and all the subsequent events were being aired. Under the sober darkness that rolled over me from the grey screens, I fell in step with the funeral march of that week and the next. What had seemed through my early twenties like a bright and hopeful future was now in question. Wherever I was bound, I knew it was not Seventh Avenue.

I experienced the assassination that followed, Robert Kennedy’s as if I had been beside him. I was watching Kennedy that night on T.V. leave the platform, the cameras following him for his walk through the hotel. I switched off the set. In the morning, as I turned the corner of Avenue A by the newsstand in front of the local breakfast place, I caught sight of the headline—RFK SHOT. The plates of the earth shifted under my feet. Just two months before, my mother whose concern about me had anchored my sense of who I was, had died. This personal tragedy and the national now conspired to change all my choices about a career.

Weeks after John Kennedy’s death in November of 1963, I crossed paths on the sidewalks of Manhattan with a fellow student a class ahead of me at college. I had dropped out of a play he was directing, and I was still ashamed at the circumstances, but he cheerfully asked what I was doing, and when I confessed to being without a job, he insisted that I apply to American Heritage. He was writing for one of the magazines they published, Horizon, a glossy hardback survey of arts and letters, and working on a cookbook for Heritage based on American recipes that stretched back to the Colonial period. To my surprise, after an interview, I was hired.

I didn’t write for the prestigious pages of American Heritage’s series on American history and their lavishly illustrated pages, or on Horizon, but on a new project which would be sold in supermarkets, a series of thin, easy-to-read books marketed not to history buffs, or for the coffee tables of upscale homes that wanted some intellectual content displayed, but to the average shopper. Every state in the union would get a separate hardback volume of easily digested information, well illustrated. It would be sold as an Encyclopedic Guide to the United States. Each of the writers was given at least one state (mine was Arkansas), and we were asked to pick a section that would run through all the volumes, state flag, state flora, state birds, animals, and I with an intuition that in retrospect surprises me, chose the state’s folklore. The general editor for the series was an expert on Native Americans and though he shook his head in our first general meeting, remarking astutely that I was a square peg in a round hole (or the opposite) my partiality for the folklore of the Native Americans brought me some credit. I gradually learned the trick of writing simple, straightforward copy in short sentences and absorbing a host of information from other places so as to meet the weekly deadlines. Soon I was skillful enough to take off for archives of the American Folklore Society’s journals at the New York Public Library, where in addition to reading every book I could find on American folklore in general, I acquired the equivalent of an M.A. in that subject.

Whatever sort of peg I was, I didn’t fit at American Heritage and so when the project was over I took my leave and found myself again on the unemployment line, but this time with a bank balance that would tide me over and a much larger weekly check from unemployment insurance.

I owe more to that line however than the checks I received, particularly during my first bout of begging for benefits in the fall of 1963. It gave me a sense of fellow feeling for all those who had no parents or formal education to fall back on, “the insulted and injured” who held out open palms for a government handout. The characters in my first novel no longer seemed funny to me. They were hurt. The stories were longer, and they followed the trajectory of their broken hopes. They were men and women from my father’s world. He loved “characters,” was one himself, but his stories of the unhappy lives who came into his office had an underlying sadness to them. He spent the greater part of his time trying to help without any compensation, those who had given up hope. Years later, long after my father had passed away, I understood that his laughter was a way of hiding from me that it was his story I was telling.

In the summer of 1964, a junior editor at Simon and Schuster who liked me but not my novel, dismissing it as worn-out Jewish material, secured a fellowship for me for two weeks at the Breadloaf Writer’s Conference in Middlebury, Vermont. There, two important American poets fell in love with the book. Their magical words gave me hope that I ought to go on writing. Shortly after I left American Heritage and began to direct in earnest. I staged a series of medieval mystery plays at Saint Mark’s Church in the Bowery. At some point that year, visiting one of my two mentors at college, in a fit of pique and unable to find a publisher for the novel, I threw its pages on the floor of his Cambridge living room. William Alfred, a playwright and professor of Anglo-Saxon, whose stories of childhood had turned me back to my own, stooped down to the well-worn carpet, and on his knees retrieved its pages. “No, no,” he assured me. “Let me send it to a student of mine.” Just weeks later, I received a note that made me blush, accepting it at Macmillan, a publishing house which was one of the most prestigious in America at that time. Its limestone interior on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, its grand circular staircase hung with photographs of great literary figures would leave me as dazzled as a frog turned into a prince ascending the steps of his bride’s palace on their wedding day.

From that moment on, I knew what hopes I wished to come true.

There are images that float through one’s head like clouds, tinted with sun and blue skies that presage warm rains and the green of spring. Some of mine did happen and were better than any of my fantasies. Others speak to the inevitable disappointments, the defeat of youthful expectations, and as I grow older, reckon up what I have accomplished, what I won’t, I have to shake them off, go on anyway, but the bag of the latter gets heavier.

Why did that tiny man with the bag of shmutties visit me for a moment in the dawn? Was it an image of myself, with so many manuscripts, unpublished on the shelf, like bolts of cloth that no one would buy, pages that I had invested years of time in but which just gathered dust?

Or was it a more painful recognition? My father had been brilliant in his forties and fifties, serving in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, writing some of the most important legislation of that period, laws that finally put women on juries, the Fair Employment Law, as Chairman of Education passing the budget that turned the University of Massachusetts from a small state school, into a real university. At the end of that career he lost his hold on what was possible. I can’t say that he lost his grip on reality. What is “reality” but what you can carry out of dreams—what skill and luck make happen in a world outside your head; what you manage to see happen there? At the end of his life, my mother, my sister and I watched him run after dreams that we knew could never find a place in the world he walked through. More and more his face took on the shadows of a shlepper. He chased political offices he could never be elected to, haunted streets where people who had been glad of his handshake, walked away when he stopped, shaking their heads. I fled Boston after just a few weeks of living at home when he was in the midst of one of these campaigns; my chest crushed watching the humiliation of a father who had always been the guiding authority of my imagination. He was canny though, almost to the very end, despite the small strokes that confused his memory. He could rally and assume for a few hours the shape he had once had, and yet the threat of his losing that capacity frightened me and drove me into nightmares.

I know now who the tiny man with the bag of shmutties is, though in the corridor I only sensed the ghost of a familiar fear.

It was neither my father, nor me, but a ghost out of those streets where his political career rose and fell, the same Blue Hill Avenue whose taint of melancholy had followed me from adolescence into adulthood. It spoke to the wisdom of so many of his clients, and the hopeless young men who grew old trading stories and tips on the horses in the wide windows of its major delicatessens, or huddled in the booths of the all-night cafeteria just down the Avenue. They sat through the late night shifts of taxi drivers and the early risers, going out with trunks full of samples to Boston’s suburbs and beyond. Those who could barely make a living and those who couldn’t sat there until the whole district emptied out, just as the Bronx did, but where did they go when the doors closed forever? They might as well have joined the ten lost tribes. The ghost I saw when I was just twenty-four on one of the Fashion Industry’s palatial floors, still clung to something in his bag, though what he knew about his own material was a mystery to me. I think the laughs had been pressed out of him too many times but if not, maybe he would have contracted his cheek as I did when I heard the sour flip to the conventional reassurance in Yiddish, to a tale of woe, a hearty, “Abi gezunt? As long as you’re healthy!”

“Abi gezunt— As long as you’re healthy, dos lebn ken men zich alleyn nemen! you can always take your own life.”

Mark Jay Mirsky has published thirteen books, among them the novels, Thou Worm Jacob, Proceedings of the Rabble, Blue Hill Avenue (Recommended in the New York Sunday Times and listed as one of the “essential books of New England” by the Boston Sunday Globe), The Red Adam, and Puddingstone as well as an early collection of novellas and short stories, The Secret Table. Among his non fiction work is My Search for the Messiah, Dante, Eros and Kabbalah, The Absent Shakespeare, and a memoir, A Mother’s Steps. His work has regularly appeared in literary magazines like Partisan Review and The Massachusetts Review. He was for a time writing reviews of fiction for the Washington Post’s Book World. He is also Professor of English at the City College of New York and the editor-in-chief of Fiction, a magazine he founded in 1972 with the American writer, Donald Barthelme and the Swiss novelist, Max Frisch.