Paterson

by Tema Stauffer

The city of Paterson, near the Great Falls of the Passaic River in New Jersey, was founded in 1791 by Alexander Hamilton and others as the nation’s first planned industrial city. Its textile mills and factories would help establish America as a key player in the Industrial Revolution.

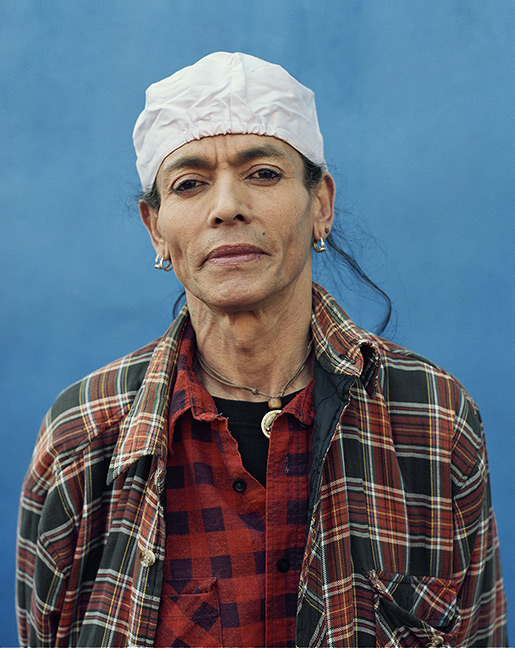

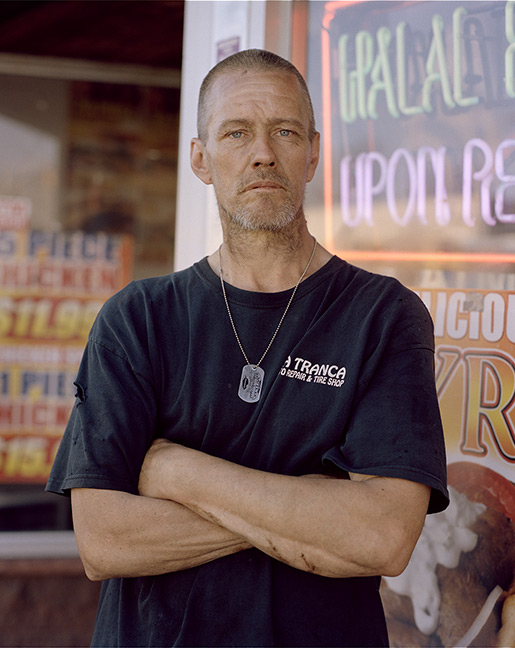

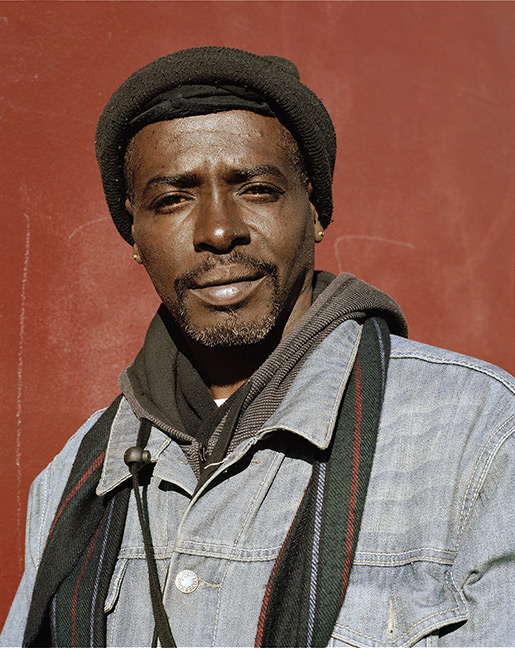

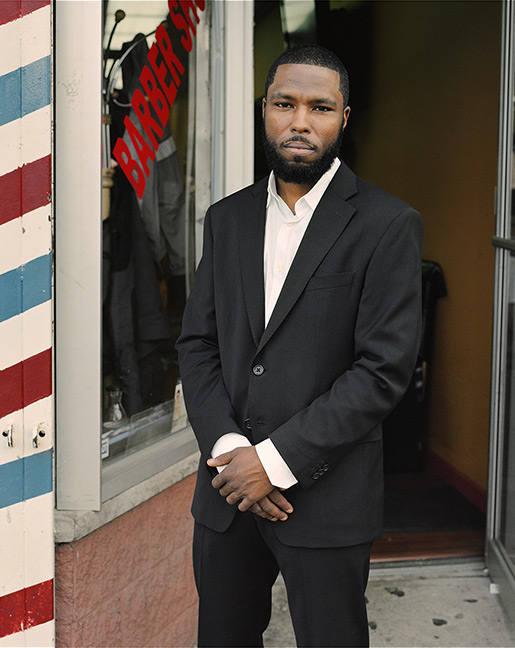

In 2009, Tema Stauffer was passing through Paterson on her way somewhere else. The industries that had once made the city prosper were long gone. Tema was struck by the architecture that remained standing in contrast with the present’s harsh social and economic reality. Intrigued, she would return to the city over the next five years to make portraits of the diverse group of people—proud and resilient—that have made this post-industrial city their home.

We ask Tema about the people that she met and the books she read that helped her better understand Patterson.

Literature is one source of inspiration for the places you’ve chosen to photograph. You call it a “roadmap.” For this series, you read two novels set in Paterson, New Jersey: Junot Diaz’s “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao”; and “Terrorist” by John Updike. How did the characters, setting and themes of these two novels inform, support or negate your vision for the Paterson series?

Both novels focus on the experiences of social misfits, though Junot Diaz’s Dominican-American protagonist, Oscar, is a more sympathetic character than John Updike’s Ahmad Ashmawy Mulloy, an alienated high school student who nearly commits an act of terrorism. Oscar is an overweight science fiction nerd with a big heart and an urgent desire to express love, utterly lacking the machismo of his peers. Ahmad, on the other hand, is driven by his growing contempt for what he perceives as the shallowness and materialism of the American way of life and turns to a dangerous form of religious extremism for answers. Reading these novels collectively gave me more insight into Paterson and the emotions, struggles, and tensions present in such a racially and ethnically diverse city; one that has been faced with significant economic decline since it was long-ago a magnet for immigrants seeking job opportunities.

You spent about five years connecting with the town of Paterson and the people you photographed, soliciting and gathering your subjects’ stories. At one point, you had considered including those stories in the series, but you chose not to. How did you strike a balance, if you did, between the story you wanted to tell and the stories your subjects told you?

I think it’s more accurate to say that I solicited the portraits and the stories followed naturally. Each conversation began with me introducing myself and asking a person if he or she would be willing to be photographed, and in the process of us making these portraits, people often did open up to me and share their stories. I wrote down pieces of these conversations, but mostly made mental notes, which I remember clearly to this day. I didn’t ask people for interviews, so these conversations certainly shaped my understanding of and empathy for each individual and how to portray them, but did not become the work itself. In some cases, I got to know people in stages over the course of years – through longer conversations and photographing them more than once or twice. At times, it was also important just to talk and not take pictures. The viewer can interpret their stories from reading what is conveyed in the photographs rather than information about their lives.

Did you ever feel that there was something you perceived about a person or a place that remained elusive, closed to the camera, something you couldn’t quite convey through the lens?

Of course some people I approached were not interested in being photographed, so the portraits you see come from the exchanges that did happen. There was a woman in particular I noticed on countless afternoons waiting for the bus in the same spot on Main Street. The depth of expression in her face made such an impression on me, but she didn’t want to be photographed. With those whom I did photograph, these encounters generally started with a degree of initial awkwardness, so creating an intimate space with each person on the street was essential, as well as shooting a lot of frames to arrive at moments in which people let their guards down and revealed more subtle and nuanced emotions. Connecting with people, listening to what they had to say about their lives, and establishing trust and openness was all part of what inspired me to spend so much time on the streets, but none of this came quickly or easily.

With fiction, we close the book and the author hopes that something vital of the story stays with us. What do you hope stays with the viewer of “Paterson?”

There are many photographers’ portraits that resonate with me such that the people they have photographed live with me like people I know. I am curious and moved by their lives and identities and they become part of my consciousness. So I hope that these portraits reflect compelling individuals who will similarly remain in viewers’ minds as people who exist to them. Made in the years following the economic crisis, these portraits also speak to increasing economic disparity in America and attempt to bring a visible reality and human face to an understanding of pervasive unemployment, poverty, and hardships in post-industrial cities like Paterson.

Tema Stauffer is a photographer whose work examines the social, economic, and psychological landscape of American spaces. Her work has been exhibited at Sasha Wolf, Daniel Cooney Fine Art, and Jen Bekman galleries in New York City, as well as galleries and institutions internationally, including the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. In 2010, she was awarded an AOL 25 for 25 Grant for innovation in the arts for her combined work as an artist, curator, and writer. She was a finalist for the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition 2013; she was also the recipient of the 2012 Women in Photography – LTI/Lightside Individual Project Grant and a 2014 Workspace Residency for her documentary portrait series, Paterson, depicting residents of Paterson, New Jersey during the years following the American economic crisis. She received her BA from Oberlin College and her Master’s degree in photography from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Stauffer is currently an Assistant Professor of Photography (LTA) at Concordia University in Montreal.