Megachurches

photography by Nina Berman

Interview by Lucía Seda-Pérez

As evangelism and the Christian right continue to grow, so do their houses of worship, blooming into megachurches that can hold anywhere from two thousand to forty thousand congregants at a time. Often resembling malls or cities within cities, they offer services that go beyond the spiritual needs of their multitudes from health clubs to shops and even a major coffee house franchise.

Between 2004 and 2005, documentary photographer Nina Berman traveled across the United States to see these churches first hand. She provides an inside look at these “supersized sanctuaries” and perhaps some clues as to why evangelism continues to gain momentum.

The following interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Big Jesus statue at Solid Rock Church

A megachurch with 3,000 members, in Monroe, Ohio. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

The Lakewood Church

Joel and Victoria Osteen at the grand opening of Lakewood Church’s new Central Campus. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

New Life Church

Kevin DeWeber, 39 and his son Jayme DeWeber, 13 are also known by their Adventure Ranger names, Pine Martin and Turtle. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

Southeastern Christian Church

The lobby of the Southeastern Christian Church, the 7th largest megachurch in the US, with 25,000 members. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

Southeastern Christian Church

Church members arriving for Sunday service at Southeastern Christian Church. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

Southeastern Christian Church

Children leave bible class after Sunday service at Southeastern Christian Church. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

Southeastern Christian Church

The bookstore at the Southeastern Christian Church. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

New Life Church

Sunday prayer service inside the New Life Sanctuary. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

New Life Church

The organization “Youth With a Mission” (YWAM), based in Monument, Colorado, holds a missionary event on Ethnic Day during Sunday services at New Life Church. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

New Life Church

Members of the Royal Rangers outside the Worship Center at New Life Church. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

United States Airforce Chapel

United States Airforce Chapel , Colorado Springs, Colorado, USA. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

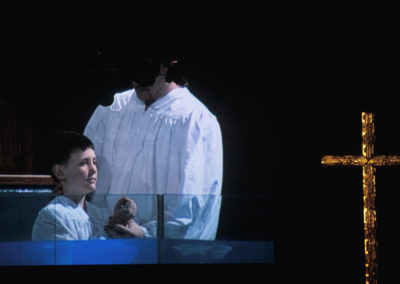

Southeastern Christian Church

Sunday service at Southeastern Christian Church. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

New Life Church

Pastor Ted Haggard, founder of New Life Church. Haggard resigned from the church in 2006 amid sexual allegations. ©Nina Berman/NOOR. All Rights Reserved

How did you become interested in megachurches?

I became interested in megachurches in 2004, around the reelection of George W. Bush. There was a lot of conversation at that time about the Christian right and the Christian evangelical vote. Every once in a while, there’d be a random story about some giant megachurch. So, I thought to look more intentionally at this phenomenon and why they came about, what they provide for their members, what they look like, how they transmit their ideology. At the time, I worked with a U.S.-based German writer, and we pitched the ideas to a magazine called German Geo which published some of the work.

Your work often addresses issues that are not part of the national conversation. What story about megachurches did you want to tell?

First, I wanted to show what they were. I wanted to show that it’s a pretty locked-in society. If you go to a megachurch, you don’t really have a whole lot of contact with the outside world. The people that we talked to, their friends tend to belong to the church. They marry within the church. If you asked them what they were reading, they were reading books sold in the church library. It creates this sort of bubble that has a certain aesthetic. The aesthetic was also interesting to me. And my concept is that the church has kind of become a town. In the U.S., we have defunded so many activities and institutions that formed our civic society and, in its place, have developed religious institutions to provide for those needs. If you are out of a job, you don’t necessarily go to the unemployment center in your town. You go to the pastor. That’s a major change.

What do you think is their appeal?

I think that if you are living in a suburban or ex-urban space, it can be quite alienating. There is definitely a draw to going. Me and the reporter went to New Life Church in Colorado Springs, a couple of times, and we thought, wow, if we lived in Colorado Springs maybe we’d even join New Life. People hunger for community. American society can be a particularly fractured, alienating one because people are moving around, and the country’s so big. And if you have no center in your community—there is no downtown in many places, there’s just Walmart—where are you going to go for communal life? You’re going to go to that big entertainment castle down the road, right?

Right.

It provides a need. Of course, there are dangers. Many of these churches are preaching a prosperity gospel and evangelical beliefs that vary between ultra-homophobic and ultra-Islamophobic. The pastors tend to be exceedingly wealthy. In some ways, it mirrors a perverted capitalist structure. At the one church we went to in Louisville, Kentucky, [Southeast Christian Church] they collected $800,000 in a weekend. Which is one picture they wouldn’t let me shoot! You go to church, and it’s like ‘where is the religion here’? It’s like an insurance building.

There are several pastors who’ve been busted for preaching anti-homosexual sermons, and then it turns out they’re closeted gays. Or while they’re preaching love and all that, they’re skimming from the church. These churches don’t pay taxes, so there is a whole financial incentive to going down to a vacant strip of land, declaring yourself a pastor, setting up shop, and collecting income. I often thought of trying to set up a church myself because it’s a super nifty little tax scheme.

It’s like a business.

With these megachurches, you don’t go to the local gym in town; you go to the gym at the church. If you want a Starbucks, you don’t go to town; you go to the church Starbucks, which has got a franchise inside the church. There is merchandising, tapes, books, sweatshirts — the whole shebang. It’s a brilliant little business, of course, it’s got its implications.

With the enormity of these arena-sized churches, seems like it would be difficult for members to connect with each other or their church leaders. Like it can sometimes make people feel anonymous. Do you think it’s possible to find a sense of intimacy and tight-knit community inside these “supersized sanctuaries?”

Each church has its own aesthetic and script, and it’s always interesting if you can sit through a couple of sermons because it very much resembles a political candidate’s speech where they just replay the same thing. There is often music, which makes people feel vibrant and alive and then you’re looking around, and there is 8,000 or 12,000 of you all singing the same thing—that’s a powerful emotion. There are usually really good lighting effects. There’s a dramatic narrative to this sermon—very different from Catholic sermons. And then at some point, it could be ‘who amongst us wants to dedicate themselves to Jesus? Come on down.’ And this is a moment of revelation and excitement. Or there’s a baptism. There is a whole narrative art to the sermon, which keeps people engaged. And then you have to join the small weekly groups, which is where bonds are cemented. Then there is missionary work. There are pictures from New Life in Colorado Springs where you have people dressed up; women in Afghan burqas, people dressed up in all sorts of nationalities as symbols of who out there needs to be converted. The idea that there are Christians in the world being persecuted is part of the narrative. There are usually bands for high school kids. If you go to church, you probably send your kids to the church school. We saw one church [class] for toddlers called “Pat the Bible.” They are getting the feel of the Bible before they can speak.

Like tactile learning.

Which is a powerful form of transmission of a particular type of ideology. I am not saying I am critical of this ideology; I am saying this is what it is. And there are tens of millions of people in the United States who probably support this. I don’t know how many people actually belong to megachurches, but the Southern Baptist Convention apparently represent 40 million people. Many of these [megachurches] are connected to the Southern Baptist Convention which is a very conservative right-wing force in American society.

It’s not just the service, the extracurricular activities or missionary work that informs the everyday life for some people.

The next [step] is advocating for political candidates inside churches. What used to be sort of quietly said, can now be said openly. Which is, you know, “homosexuality is a sin, and should never be allowed. Therefore, vote for Ted Cruz.” Before they couldn’t say “Vote for Ted Cruz” but what they could say is, “make sure you go and vote!” And what that probably means is that candidates in the future would be able to actually hold events in these churches. Why not? If the church is allowed to have a political speech inside the church and advocate for a candidate, then that would be the next step. So, I don’t know if that will pass muster, but that’s where society is going.

Now you experience politics in your house of prayer.

Exactly. And so why do you need a public school? Why should you pay a tax for a public school if you’re sending your kids to church school? You don’t want to. And that’s what the whole defunding of civic institutions that I talk about. You know, there’s something called—then it was called the ‘Christian Phone Book,’ I don’t know what they call it now in the mega-internet age—but, if you wanted to hire an attorney or you wanted a plumber, you would look in the Christian Phone Book. God forbid you hired someone who wasn’t Christian. People can’t believe that. But it’s absolutely the case. Because then you know that they can be trusted. Because they share your ideology. So you can kind of imagine where this all leads.

Right. It’s becoming even more and more hermetic if you’re directly trying to avoid people who don’t share your religious beliefs.

Yeah. They shouldn’t live in your town. Basically that’s where it gets to. They shouldn’t live next door to you, they shouldn’t live on your street. They shouldn’t work. You should go and bomb them. A lot of this material is in a chapter in my book Homeland. There’s a connection between militarism and fundamentalist Christianity which plays out in some of these churches, for example, the Royal Rangers pictured in the series.

We were captivated by the photographs of the children being baptized, praying, the ones in uniform pledging allegiance, those scenes are very powerful.

It’s interesting to see how ideology is transplanted from one generation to the next. Children are exaggerations of adults in a strange way. You can see the belief system of an adult through how they construct the world of their child. Once you’re given these beliefs—and everyone’s parents give them some belief system—you can see it in the rituals and in the clothing and in the gestures. One day that person will grow up to be an adult. And what are they going to believe? The Royal Rangers is the Christian version of the Boys Scouts. I walked into that room, and it just reminded me of Brownshirts, of Nazi-sort of Brownshirts. Now, they are not Nazis—not that I know of—but the symbols, the colors, the look… I think it comes through without saying it. And in the other picture, there’s a boy and a girl marching. They’re in school, they’re walking down a hallway, and the mural on the wall is the American flag and the Christian flag, but the Christian flag is bigger. So, the idea is that America is a Christian country, you give allegiance to a Christian god, to Jesus Christ.

It supersedes your belief in America, metaphorically speaking, just by having the Christian flag be bigger than the American flag.

Totally. And when I say American I mean the Constitution and certain privileges offered by the Bill of Rights.

What kinds of conversations do you think your series invites viewers to have?

Oh, I don’t know. I really don’t know. I don’t think about that too much. I think people are still just startled when they see them and can’t really believe that these places exist. And when I look at them now, I think it just seems so normal and ordinary, but that has been my experience. Things that seem super bizarre ultimately just become normalized all the time. I mean, now they’re doing weapons’ training inside churches.

When we first looked at this series we were surprised to see that you’d done it over a decade ago. Would you consider revisiting it now with a different eye?

I don’t think I would revisit it unless there was a particular church… You know, there are some really exploitive pastors who go into the poorest communities and do an ideological shakedown of members. In Atlanta, there’s one particular guy—his name truly is ‘Creflo Dollar’ —and half the sermon is just, ‘You are a sinner. You are poor because you are sinners. And you are sinners because you are not giving to a church, so step it up.’ That is the language. And so, if I were to do more of it, maybe I would focus on this kind of predatory capitalist aspect as opposed to this kitschy, weird, Christian bubble aspect.

It’s a more sinister and blatant aspect of explicitly blaming people’s economic situation on their lack of faith.

That’s what the prosperity gospel is. It’s another version of “pull yourself up by your bootstraps,” and “everyone has a chance to make it in America.” It denies all structural oppression, inequality, everything. It’s like ‘You are the problem. If only you gave your life to Jesus’…and the way to give your life to Jesus is to show your respect to the church by coughing up some money. That is it. We’ve exported this American evangelical ideology. You see it all around the world: in Uganda and Central America. It’d be super fascinating to actually do some kind of investigative project as to the connection between these Evangelical churches and American business interests. I think it would be quite useful for people to understand all of these pastors and these places.

Nina Berman is a documentary photographer, filmmaker, author, and educator. Her wide-ranging work looks at American politics, militarism, post-violence trauma, and resistance. Her photographs and videos have been exhibited at more than 100 venues including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and Dublin Contemporary. She is the author of Purple Hearts – Back from Iraq, portraits, and interviews with wounded American veterans, Homeland, an exploration of the militarization of American life post September 11, and most recently, An autobiography of Miss Wish, a story told with a survivor of sexual violence and reported over 25 years. Her work has been recognized with awards in art and journalism from the World Press Photo Foundation, Pictures of the Year International, the Open Society Foundation, the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Aftermath Project, the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University and Hasselblad. She is a member of the photography and film collective NOOR images and an associate professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism where she directs the photography program. She lives in her hometown of New York City.