Roberts, David. Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives. 1839, The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Jerusalem Stone

by Anne Da Vigo

A man in mirrored sunglasses standing by his car called out to them at Jerusalem’s Lion Gate. “Excuse me ladies, you like tour of Mount of Olives?”

“How much?” Karly said.

“Two hundred, very reasonable. I show you all sights. Garden of Gethsemane, Tomb of the Virgin, Church of Mary Magdalene.” He might have been attractive if it weren’t for his bad teeth and a large mole on the right side of his face.

Sharon leaned heavily on Karly’s shoulder and whispered in her ear. “He looks like a terrorist.”

Karly ignored her older sister. “One twenty.”

The guide straightened his spine. “Two hundred.” He patted the dented fender of his Volkswagen Golf as if it were a fine camel.

Karly agreed. She was a thin, wiry woman, who wore her hair scraped to the crown of her head and anchored with a rubber band. She’d come on this trip to Israel after their mother, Mariah, had called to badger her.

“Come on, Babe. Patch it up. Sharon’s bad.”

“That’s what she told you?”

The telephone crackled as Mariah exhaled a lungful of what Karly assumed was marijuana smoke. “Not in so many words.”

Karly had recently separated from her husband, and a few days after the call she began to dream about Sharon, two or three times every night. She awoke with a feeling on her skin that Sharon had touched her.

Inside the cab, Sharon closed the windows and asked the guide to turn up the air conditioning. She’d always hated the heat. To escape the odor of the driver’s sweat and aftershave, Karly opened the window on her side.

They dipped into the Kedron Valley where the guide pointed out the burial place of Absolom, King David’s rebellious son. The small car was soon panting up the Mount of Olives. As he drove, the guide introduced himself as Suleiman.

Sharon brightened. “The Muslim variation on Solomon, David’s good son.”

Suleiman told them his wife and eight children lived not far away, on the south side of the Mount of Olives.

Where the groves had once flourished, the Mount of Olives now was tightly packed with houses, churches, religious schools, and cemeteries. The approach to the Garden of Gethsemane was jammed with idling tour buses spewing exhaust. Suleiman coaxed the Golf, inch by inch, into a space the size of a coffee table.

Of the garden’s dozen remaining olive trees, only one twisted relic looked old enough to have dropped its hard, green fruit at Christ’s feet.

Sharon whipped her pocket edition of the New Testament from her purse and thumbed the pages to Mark: “They came to a small estate called Gethsemane, and Jesus said to his disciples, ‘Stay here while I pray.’”

As if to screen out Sharon’s religious claptrap, Karly donned her sunglasses. She hardly recognized this bulky woman in a floppy sun hat and rubber-soled walking shoes. Karly’s memories were of a skinny-legged seventeen-year-old with big tits who played eight-track tapes by The Knack and danced on her bed to “My Sharona.”

They’d shared a bedroom from the time they were toddlers, but their closeness ended when Sharon was seventeen and Karly thirteen. That year, Sharon stole the $250 that Karly kept in a cigar box under her bed. It had taken Karly five months to earn the money babysitting on weekends, hoarding every dollar to buy a Nikon. The school yearbook needed a photographer, and the camera, she hoped, would be her passport into the closely-knit group of kids on staff.

The money, Sharon, and the yearbook slot all disappeared. Karly learned from Mariah five years later that her sister spent the cash on meth. Sharon hitchhiked around the country, became an addict and eventually entered rehab in Portland. The minister who operated the halfway house became her husband. Hugh fell in love with her, Karly suspected, in equal measure for her conversion and her cantaloupes. Sharon and Hugh had been married twenty-five years now and had four children. Karly had never met them. After Sharon left, Karly refused to see or talk to her. Anger from the early years solidified into a hard, protective shell. Mariah called Karly occasionally with updates on births, soccer trophies, and graduations. Karly barely listened.

Sharon closed the Bible. They piled back into the car and climbed further uphill to a small, contemporary church perched near the mountain’s crest. “At this spot,” Suleiman said, “Jesus broke into tears as he gazed across the valley at the Temple in Jerusalem. He foresaw its coming destruction by the Romans and was overcome with sorrow.”

When the sisters entered the church, Sharon opened her Bible to Luke.

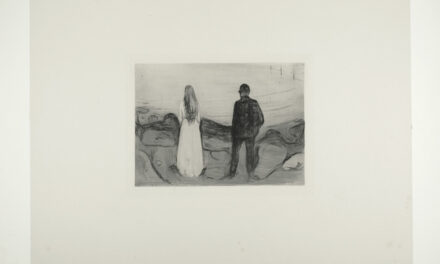

Karly veered away from her toward the church’s arched front window, which framed a view of Jerusalem. She’d read that the city required all buildings to be faced with Jerusalem stone, a whitish limestone used in the construction of the Temple in Jesus’ time. The stone gave the city a cohesive look, as though its structures sang a concordant psalm. The sun had sunk low, but heat still radiated through the glass. As she watched, Jerusalem began to gleam with an extraordinary golden light. It touched first the tips of the steeples and minarets; then crept downward over the roofs and walls until the entire city shimmered.

A director of television documentaries, she knew this was the moment of Long Light, the best possible time for filming. The phenomenon depended on the sun’s angle, the thickness of the atmosphere, and the range of the color spectrum. She often gathered her crew in anticipation of the twenty or twenty-five minutes of low sun when colors set the viewer’s mind and heart ablaze with hope and possibility.

It was the science, the physics of Long Light that must have evoked Jesus’ tears, yet her own throat was blocked and tight. She stumbled outside, where the air tasted of dust. Perspiration pricked her skin, and in a few seconds her blouse was soaked between the shoulder blades.

Christ was a sentimental fool, she thought defensively, a little ashamed of her emotion. Beauty lasted only until it was wiped away by the next fire, flood, earthmover, divorce, or layoff. Tears changed nothing. Christ knew temples were built and demolished at the whim of emperors and despots. Yet he wasted his tears on the coming destruction of the lovely temple he saw from this hill. No matter how much he knew, his connection to this place sidestepped logic.

When she and Sharon were young, they had their fill of beautiful places. Mariah was a nomadic ski instructor who dragged her daughters from Aspen to Stowe, from Alta to Tahoe to Vail. With each move, Karly felt robbed of familiar landmarks: the hill where she received a scar on her knee racing her in-line skates, the scent of lilacs in the park where she kissed her first boyfriend. Her history had been stolen from her, time after time.

She smelled cigarette smoke and glanced over her shoulder to see Suleiman.

“You like this place, yes?” he asked.

“Very pretty,” she said.

“You don’t like.”

She blinked, surprised that, despite his bad English, he was perceptive. “It’s just a place, Suleiman.”

His cigarette ash glowed. “My grandfather, he lives with us. Every day, he watches sun come up. He cries for his little farm on West Bank. Jews have built apartment house there.”

“He cries? He doesn’t wish they were dead?”

“Perhaps he does.” He crushed the butt under his heel.

Light faded quickly and a sad, gray haze settled over the city’s stones. Loudspeakers in a nearby mosque snapped on, the call to prayer quivering in the evening air.

***

The next morning, the 4:15 call to prayer jolted Karly awake. Their guest house in the Muslim Quarter of the Old City faced a mosque, and through the open window the muezzin’s voice blared on the public address system. In the twin bed across the room, Sharon’s limbs jerked. She moaned in her sleep.

Karly punched her pillow and studied her sleeping sister in the mosque’s green neon light. Since Karly had last seen her, hills and canyons had transformed her sister’s face. Her eyes were surrounded by thin, discolored tissue. Under the sheet, her humped bulk resembled an undersea creature. She could have been a stranger, yet they were sharing a room again.

After the muezzin ended his chant, Karly’s eyes refused to close. Sharon awoke near dawn. Her forehead wrinkled as though she were trying to remember who Karly was. Then she nodded and slipped her hand under her cheek in a gesture Karly remembered.

“There’s an island in the blue, blue Pacific…” Sharon’s voice was husky with sleep.

“…it’s our island and on this island there’s a house,” Karly answered unwillingly.

Sharon had invented this game when they lived in a shabby apartment in Aspen. The girls were teenagers by that time, past the age they believed Mariah’s pallid promises about settling down after one more winter. As they lay in bed each night, they had embellished the fantasy—a fabulous home where the two of them would stay forever.

“I have a huge water bed in my room with black satin sheets and a mink throw,” Sharon said. When Karly didn’t answer, she raised her eyebrows.

“That wasn’t it,” Karly said finally. “It wasn’t your bedroom, it was our bedroom. The two of us.”

“I don’t remember that.”

She should have, because Sharon pretty much raised Karly. She bought the Stouffers frozen turkey dinners and made Karly’s dentist appointments. Kids who hazed Karly because she was new—boys who pinched her nipples and girls who stuffed bloody maxi-pads in her locker—regretted it when Sharon caught up with them on the way home from school.

Every night, Sharon eased their loneliness by enticing Karly to play the island game, giving them both an opportunity to dream.

But Sharon disappeared. For the remainder of the ski season, Karly huddled under the blankets with her back to the other twin bed, stripped to the bare, striped mattress. The wind soughed in the pine branches outside her window. Sometime after two when the bars closed, her mother arrived home, often accompanied by Gary, her ski bum boyfriend. Karly heard their smothered laughter, the flush of the toilet. Wind crept through the cracks and rattled the windows. Shoes dropped on the floor; then Mariah’s headboard shook the common wall as though it were being beaten down. Karly plugged her ears, but she couldn’t shut out the sounds: the thumps, the squeak of the bed frame, the words, filthy words she never had heard, the moans and long, drawn-out cries. The wind blew frozen pellets of spring snow against the glass. She grabbed handfuls of her hair and twisted them in her fists until her scalp throbbed. During the day, she cried immoderately over small incidents—a frayed shoelace that snapped in her hand, spilled hot chocolate that made a rusty stain on her clean white notebook page. When a boy in her class—an overbearing bully she hated—died in an avalanche, Karly wept until she couldn’t talk.

The summer after Sharon ran away, Karly spent the hot months with her grandfather in Sacramento. He owned a cigar shop, where Karly worked mornings ringing up purchases and restocking shelves. The customers’ good-natured teasing and her grandfather’s awkward hugs eased her back from despair. The next winter Karly and Mariah moved to Jackson Hole, where Karly enrolled in a high school film class. She began to write scripts, heft the big camera to her shoulder, and edit tape. She didn’t cry as often; but her face was tight and achy.

***

The Sisters of Zion, the French order that operated the guest house, offered breakfast, but Sharon wasn’t hungry. Karly sat on the veranda beside a group of Italians and gulped a cup of coffee. At an umbrella table, Sharon tapped out a message to her daughter, Oriana, on her cell phone. Oriana was she and Hugh’s only child still living at home.

Acid in the coffee and the smoke from the Italians’ cigarettes nauseated Karly. How was it fair that Sharon, a thief and reformed druggie, had an attentive husband and four children? Karly, who stayed, had eked out a living with her mother and earned her own way through the University of Colorado. Her soon-to-be ex-husband already had consulted a lawyer; it had been six years since she dated. She had no child.

Sharon leaned over the heavy shelf of her breasts to tie her shoe. “Let’s go to the Wailing Wall before it gets too hot.” Her breath was loud and uneven. Karly’s mouth tightened like an uncharitable fist. Sharon should lose some weight.

They opened the heavy guest house door and narrowly missed being knocked down in the street by the crosspiece of a seven-foot wooden cross. Pilgrims flooded the Via Dolorosa, the Street of Sorrows, where Christ dragged the cross to Calvary. The worshippers eddied around a priest who recited the second Station of the Cross, Pontius Pilate handing over Jesus to be crucified. Pressed against the stone wall, Karly decided the pilgrims were from Poland or the Ukraine, based on the women’s stocky bodies and pale skin, and the men’s bad haircuts. Their faces looked frozen, as if they were walking to the doctor’s office. This was what sorrow looked like, Karly thought. People bore their hurts and disappointments until they were as familiar as pinched toes.

The Old City was built on hills, and the streets fell and rose in a series of worn steps. Muslim boys in blue uniform shirts darted through the crowd on their way to classes at the madrasa. In a shop window, Karly caught her dim reflection and saw that her face bore the same lines of long-accustomed unhappiness as the pilgrims’. At the bottom of Via Dolorosa, the street joined El Wad, the Muslim Quarter’s main pedestrian thoroughfare. Two Israeli soldiers, boys with soft chin hairs, guarded the intersection, their automatic weapons propped diagonally across their chests.

The early morning light left the streets in shadow, but her film-maker’s eye caught a shaft of sun slipping between the east-west buildings to cast a wedge of brilliant illumination high up on a wall of Jerusalem stone. The souq stirred. Shopkeepers rolled up the metal doors of their stalls to display olive-wood carvings of the Virgin, cheap Russian Orthodox icons, cell phones, DVDs, and fake Roman oil lamps.

Tall buildings trapped the smell of deep-dug, ancient sewers and washed paving stones. Aromas of allspice and cumin floated from an open-air food shop where a cook fried kibbeh in hot oil. The smells expanded her senses, previously overburdened by calculations of light, frame, and camera angle. Her body felt lighter, and her steps quickened, leaving Sharon behind. A boy passed, balancing a board on his head loaded with freshly-baked loaves. Earlier, Karly wasn’t hungry, but the yeasty smell lured her to purchase a round loaf sprinkled with sesame seeds. When Sharon caught up, Karly broke off two pieces and offered her one.

Sharon grimaced. “There might be germs. I saw flies.”

“It’s too early in the day for flies. And the bread’s still warm, right from the oven.”

“There’s a smell.”

“Suit yourself.” Karly threaded quickly between the shoppers down El Wad to the Wailing Wall, leaving Sharon to struggle through the lava flow of old men, nuns, housewives, orthodox Jews, chanting Christians, and aggressive Muslim vendors hawking rosary beads. It didn’t feel as good as Karly imagined it would, to reverse their childhood order where Sharon always led the way. At the Wailing Wall Plaza, Sharon caught up, gasping. The hair at her nape was dark with sweat, and irregular red patches marred her cheeks.

“Is this about the bread? Sharon asked. “Here, give me a piece.” She snatched at the plastic sack containing the broken loaf.

“Too late.” Karly dumped it into a trash barrel.

“You’re hard. And spiteful,” Sharon’s heavy jowls tightened, a mother fed up with an exasperating child.

They were diverted by a band of thirty or forty people pounding drums for a bar mitzvah, the young celebrant bobbing in their midst. Rearing above the crowd was the seventy-foot remnant of the vanished Temple’s limestone retaining wall. Karly recognized the white rock as Jerusalem stone. As it had at the Mount of Olives, the stone ignited passion. Men and women, segregated from each other by an iron fence, chanted psalms, rocked on their heels, and wedged written prayers in the cracks of the unforgiving stone blocks. The Temple is dust, Karly wanted to shout. It’s gone, it’s been gone for two thousand years; all that’s left is a big, ugly wall.

Sharon jostled her elbow. “I bought tickets for the underground tour. They’ve excavated five times as much as you can see here.”

“I’m not going,” Karly said.

“It’s the closest we’ll get to the spot where Jesus turned out the money changers.”

Karly’s legs twitched, wanting away from this tourist trap. Sharon seized her arm and steered her in the direction of a group clustered around the guide, an orthodox Jewish woman who wore a long skirt and concealed her hair with a closely-wrapped scarf. Karly trailed sullenly at the end of the group, holding tightly to the handrail as they clanged down metal stairs and catwalks deep into the tunnel. Jackhammers spewed dust into the air and rattled the ground under their feet. The damp air was suffocating.

A wall of Jerusalem stone loomed above them and stretched far ahead into the darkness. They stopped at the base of one of the great, towering blocks.

“This is the largest: forty-three feet tall and weighing nearly 600 tons,” the guide said.

Karly laid her palm against the white surface. It felt benign, but she knew toes and fingers, limbs, lives had been lost to hew it, haul it, and heft it into place. As the group shuffled deeper into the tunnel, a narrow alcove opened, where a murmuring woman sat on a white plastic chair. Her face hovered so close to the wall that she could kiss it. The guide gathered everyone around her and spoke in a whisper as compelling as a prayer. “In the time of the Second Temple, the area right above us was the most sacred place in the Jewish world—the Holy of Holies. It was the ancient site of Mount Moriah, the Garden of Eden, and the place where Abraham bound Isaac.”

Beside Karly, Sharon took a shaky breath. The woman at the wall began to weep. The wail hovered in the dusty air, contagious, almost irresistible. Her own cry was forming in her throat when Sharon stumbled past her, knocking her down.

Her sister pressed her face to the stone. “I’m sorry I did it, Karly, but I was seventeen, and you’d sucked me dry. I didn’t want to be your savior, mother, nanny, or even your friend. I just wanted to be gone.”

The praying woman continued to cry. Dust stung Karly’s eyes, and construction lights dimmed.

“There was nothing for me in Vail,” Sharon said. “I wasn’t going to graduate; we’d changed schools too many times. What should I do, spend my life babysitting you? Or hanging onto that boy, Darren, who only called when he wanted to fuck?”

Over the sound of crying, Karly’s voice was cold. “I was thirteen. We were going to be together.”

“That was a kid’s dream.”

“Right. And I was the kid who bankrolled your bus fare.”

***

The next morning Suleiman bumped his car down the Via Dolorosa staircase to the guest house. For the trip to Bethlehem, he wore a new pair of shoes and an ironed shirt. When Sharon and Karly were settled inside, he backed the Golf up the steps to an alcove wide enough to turn around.

From the Lion Gate, they followed the ring road outside the Old City wall. “I show you first old way to Bethlehem,” he said. The route wound through West Jerusalem, past modern buildings constructed of the same light stone as the underground wall. He stopped a short distance from a pedestrian crossing to the Palestinian Protectorate. Muslim women in scarves and black dresses moved slowly past armed soldiers into Israel.

“Before, we drove straight to Bethlehem, right here, very close. Now, cars must go twenty kilometer detour,” he said. “It cost eight dollar to walk across, and pass only good twelve hours. People who used to work Jerusalem can’t pay fee, so lose jobs.”

He wheeled the car in a u-turn. “Now we take auto road.”

A concrete wall topped with chain link fencing and razor wire bordered the highway. “Jews call it security fence. We call it apartheid wall.” His nail scratched at the mole on his cheek.

From her side of the car, Karly could see only gray concrete and glittering wire. Its aura of suspicion and mistrust seemed like a great weight on her shoulders. Sharon looked out her window at the countryside. At the vehicle checkpoint, soldiers waved Suleiman through after a few words in Arabic. The car rolled into Bethlehem, where the roads were dense with traffic, and businesses advertised in Arabic script. He seemed different here, not bent over with hands clutched on the wheel, but relaxed, his arm cocked on the window sill. He parked in a small courtyard outside a souvenir shop. Waiting there was a cadaverous man with a wispy goatee. This was Samuel, their local guide to the Basilica of the Nativity.

“You’re not coming with us?” Karly prodded Suleiman, although she knew that Muslims are discouraged from entering churches. “I was looking forward to your narration.”

Suleiman’s eyes were covered by his aviator sunglasses, but she thought she saw a quiver of amusement around his mouth. “Muslims recognize Jesus as just one of 124,000 prophets. I am not so familiar with all of them.”

On the short walk to the basilica, Samuel led the way. “The guide business must not pay much. He looks as if he needs a good meal,” Sharon muttered. When they arrived at Manger Square, Samuel warned them to watch their heads as they passed through the doorway of the huge church.

“It was built with a low, narrow door to encourage humility,” he said.

He whispered that the Basilica of the Nativity was the oldest known Christian church, built by Emperor Constantine about 330 A.D. Sooty candle smoke drifted up from dozens of votive lamps dangling, bat-like, from a high ceiling. Disappointment flooded Karly. The church was massive, yet tainted by human incursions. Gilded icons of obscure saints were blackened with smoke; the mosaic floors chipped. The odor of melted wax and burned wicks stung her nose. Orthodox priests with thin beards and pale, folded hands seemed too weak to be God’s servants. The church wasn’t saturated with spiritual feeling, even though it was supposed to be the birthplace of Christianity.

Samuel led them through the basilica and down narrow steps dimpled by millions of pilgrim feet. Sharon stooped to ease herself through the doorway. The small, airless chapel was stifling with the body heat of twenty other visitors. A dozen silver lamps hung from the underside of a small altar built over a silver star embedded in the stone floor.

Samuel murmured, “Below the opening in the center of the star is the spot where Mary gave birth to Jesus.”

Sharon awkwardly dropped to her knees at the altar and buried her face in her palms. Karly felt too ill at ease to kneel. She’d last visited a church when one of her film crew was married, and a Reno wedding chapel had been the site of her own dissolving marriage. A nun stumbled over Sharon’s feet. The old woman murmured an apology and shuffled away. After a minute or two, Sharon struggled to stand, her breath shallow. “I need some air. I’ll meet you outside.” Her skin was papery white.

“I’ll come,” Karly said.

Sharon shook her head. Samuel cupped Sharon’s elbow and helped her up the stairs.

Left behind, Karly pushed past another pilgrim. With her fingers, she skimmed the polished marble surface of the nativity altar. It seemed too smooth and elaborate. Shouldn’t it be constructed of ragged stone or wind-gouged wood? To Karly, birth was about fear and pain.

When she emerged from the basilica, Karly flinched in the light. Sharon stood with Samuel and Suleiman in the shade of an olive tree fanning herself with the brim of her hat.

“I’m here at His birthplace, the very place, and instead of praying, I nearly faint.” Her sweat glistened like tears.

“We should go back to Jerusalem,” Karly said to Suleiman. She was impatient to return to the guest house and talk to Sharon.

“There is another place to see,” he said.

“Sharon can’t make it.”

“What place?” Sharon said.

“The Milk Grotto,” Suleiman said.

Karly laughed. “What’s that? A Muslim coffee shop?”

He looked shocked. “No, no, it is cave where Holy Family took refuge during Slaughter of Innocents. King murdered males under two hoping to kill child foretold to be king.”

“We can’t miss it,” Sharon said. She and Samuel walked slowly, hugging the shade cast by the stone walls. Karly and Suleiman forged ahead.

“Muslims revere this site also,” Suleiman said. “When holy mother Mary fed baby with her milk, drop falls on rock in cave. A miracle happens, and the grindings—how you say it— crushed stone, now helps women be fertile and produce much milk.” At the mention of breast milk, he looked away.

“Do you believe the story?” Karly asked.

“My wife received some of powder before our first born.”

When they arrived, Sharon saw the stairs and decided not to go inside. Instead, she sank down on a bench near the entrance.

The grotto was carved of Jerusalem stone, producing a creamy interior light infused with golden flecks. How she’d like to capture this light on video. For a few moments she analyzed what angle might be needed and wondered how long the phenomenon would last, but soon the voice of her thoughts thinned and disappeared. Suleiman’s aftershave hung in the air, and beneath that scent, the odor of powdery rock dust. The only other visitor was a praying monk in a white cassock with curling, unshaven tufts of beard on his cheeks. The tap, tap, of rosary beads through his fingers echoed the beat of her heart.

Karly tiptoed to the deepest part of the grotto and touched the wall. She wiped her palm on her skirt, leaving white streaks on the dark fabric, but the powdery earth clung to her hand. Each particle made her skin tingle and burn. Her hand began to swell. In a panic, she put her fingers in her mouth and sucked them like a child; the taste and smell of dust pressed against her throat.

Her senses expanded like a sail filled by a great, clean wind. She could take in everything without effort: human smells, flour-like taste of powdery earth, smooth talc caked in the whorls of her fingers, odd heat in her throat, click of beads, strange golden light. Her body hummed, and she felt dizzy. One more scent or sound, and she would faint.

“Suleiman, do you feel it?” she whispered.

He shook his head. She saw his mole and bad teeth and the priest’s carelessly shaven face, but their flaws seemed the indulgently-observed faults of precious children. She wanted, urgently, to see Sharon.

Outside, the sun reigned directly overhead, and the reflection off the grotto’s blinding façade stabbed her pupils. Sharon sat in a thin crescent of shade, rubbing her swollen ankles. Her wide-brimmed hat rested beside her on the bench. She tipped her head to look up at Karly. The shade was particularly clear with the reflected light off Jerusalem stone. For a second Sharon’s puffy skin seemed to slide away, the years receded, and she was young again, even less like the fierce, protective sister Karly remembered. Instead, Karly saw a scared, desperate girl who had run away all those years ago to save her own life.

Their mother had been right, Karly realized; Sharon was very ill. The light shifted; her skin looked putty-colored, and her mouth was bracketed by lines of worry and repressed pain. Karly picked up Sharon’s straw hat off the bench and held it in her lap as she sat beside her.

Sharon nodded at Karly’s stricken face. “It’s bad. Soon to get much worse.”

“When?”

“Six months, maybe.”

“Your timing sucks.” Karly thought about Christ’s tears and Suleiman’s mole and her own anger, which she’d nursed like a child at her breast for over twenty-five years.

“Oh, yes,” Sharon said.

“Back then, I fantasized that you were dead,” Karly massaged her temples where her hair was pulled back too tightly.

“Same here.” Sharon shook herself. Her bulk shifted and lightened. “You were a stone around my neck. I wanted to be free.”

Karly set the hat on Sharon’s head, tilted the brim to shield her eyes, and carefully anchored the slide in a little hollow under her chin. “This time, I’m hiding my nickels and dimes.”

“Forget it. I’ve saved up.” Sharon propped her legs in front of her and stretched her dusty toes inside her sandals.

Samuel and Suleiman’s voices drifted over the wall As Karly and Sharon sat together in the narrowing strip of shade, Karly caught the scent of her sister’s illness, like bruised fruit. She stayed close and breathed it in.

Anne Da Vigo is a journalist and public relations professional who has published short fiction in Out of Line, Literary Mama, and Penduline Press. She has read her stories on KVPR, the National Public Radio affiliate in California’s Central Valley.