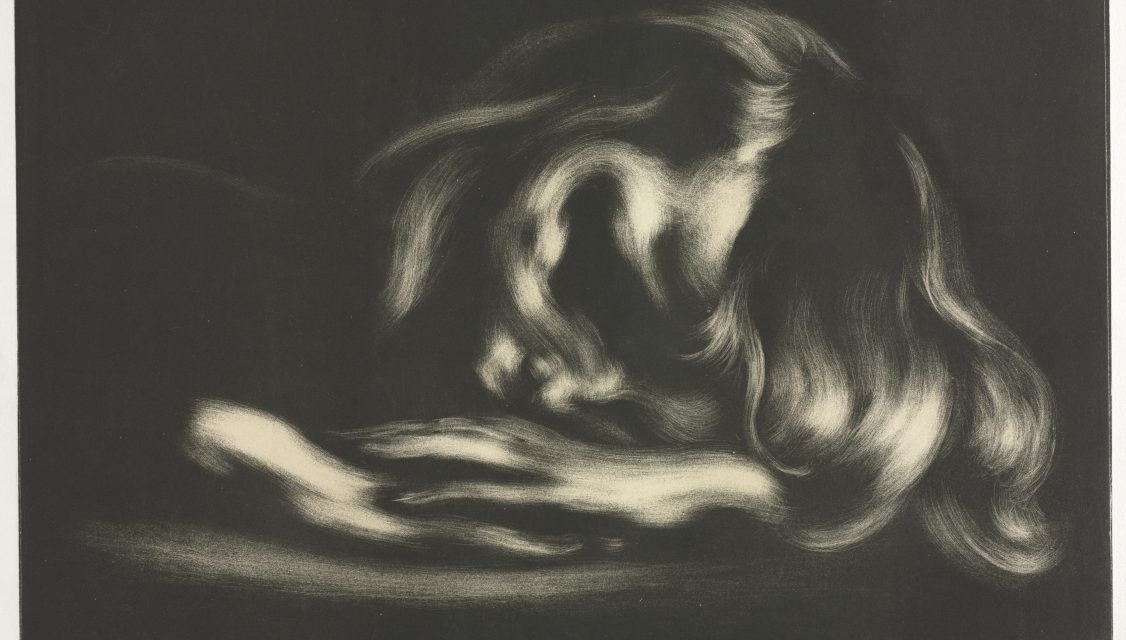

“Sleep” (Jean-René Carrière), from L’Album d’estampes originales de la Galerie Vollard by Auguste Clot. 1897, the Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland.

Dreamscape Brooklyn

by Bill Schillaci

Delia’s hand was locked around Gene’s ankle, yanking hard, yank after yank, yelling his name. One more yank by that sinewy arm and he’d be on the floor.

“Stop it,” Gene groaned.

“Are you awake?”

“I’m awake; I’m looking right at you.”

“You were looking at me before and whimpering like a puppy.”

“I’m awake, Dee. Let go of my leg.”

She did, pulling back her hand as if Gene’s leg had suddenly scalded her palm. In fact, he wasn’t awake, not fully, and when he cranked himself to a sitting position, Delia’s living room seemed to tilt weirdly and go out of focus as if separated from him by a curtain of gossamer. Despite the terror of sleep, Gene had to fight the urge to drop back into the obliteration of the couch. Delia was right, about his cries. He still heard them, anemic and weak, though they were fading, circling between his ears in a death spiral into his vault of forgetfulness. A dense, middle-of-the-night quiet watched them from the open window above Bushwick.

René, half protected behind the door to their bedroom, was also watching. She was draped in an oversized NYU tee shirt that did not quite reach below the level of her groin and, as far as Gene could tell, was otherwise unclothed. He forced himself not to stare at his sister’s girlfriend, telling himself the exposure was actually a sign of trust.

“Was it the hag again?” said René.

Gene nodded. It was the first time René referred to the creature in his dreams as a “hag,” a word she initially found degrading to women. Gene had assured her it wasn’t his invention and pulled up the web articles on sleep paralysis and its colloquial term, old hag syndrome. As she read, wavy creases formed on her forehead, and she covered her mouth with her fingers.

“It says she sits on your chest. Has that happened to you?”

“Not yet, but she’s getting closer.”

She came to him his first night on Delia’s couch, and the first time in twenty years, and then, two nights later, she came to him again. The day before he showed up at Delia’s, Sue, Gene’s girlfriend, had expelled him from her apartment in Hoboken. That had been complicated; actually it was complex, as in having many different parts, no single part fatal, but, added up, quite wondrous in its diversity, covering suspicion, misunderstanding, and disappointment, forgetting that which must never be forgotten, being too late, failing to show up at all, you said this, no I didn’t, yes you did, too much sex, too little sex, bad sex, and you ate all the egg salad. “My lunch! You ate my fucking lunch!” This had been ongoing about a month, to the point where that’s all that was left of them, where everything, every word, every action was yet one more piece of flesh stripped from what they had been. Yet they were sensible people, and they mutually tried to stop the carnage, retreating into silence and avoidance, planning as many separate nights out, alone or with anybody, people they hardly knew or hadn’t spoken to since college or cousins or aunts they didn’t like. Gene was still hoping for a miracle, but Sue, it seemed, had had enough.

“Can you stay with your sister?” was the first thing she said when he entered the kitchen. It was a July morning, midweek, the sunshine bounding in a golden glory off the river and fanning out across the ceiling. They were trying to stay out of each other’s way in the cramped eleven hundred square foot apartment on the waterfront before also trying not to walk together to their separate modes of transportation into Manhattan, Sue by ferry, Gene by PATH. And then she said it, “Can you stay with your sister?” Clearly she had planned this opening, which, in its way, was also a closing, all the introductory discussion skipped, she even went right past the conclusion – that Gene would have to go – and straight to post-breakup negotiation. As always, Sue was a model of efficiency.

“I’m really going to miss you,” he said as she shouldered her briefcase. “But not why you think I will.” This little puzzle, his final, feeble counterattack, was a puzzle to himself as well since he had no clue what it was supposed to mean. Perhaps it was a ploy to postpone his eviction, but Sue showed no interest in the bait. After she left, Gene called his boss at the NGO, explained the situation with a few embellishments and got excused for the day. He rented a van at the Avis on Bloomfield, tossed in his clothes, books, frying pan set, bedside lamp, bicycle and electric toothbrush and was in the Lincoln Tunnel headed to Brooklyn before noon.

Hours after Delia had dragged him foot first away from the hag, René reappeared, this time with the addition of in a pair of baggy camouflage shorts. She padded barefoot to the kitchen and seemed to notice Gene sitting on the couch only as she padded back, both hands lovingly wrapped around a mug of Delia’s nuclear French roast. It had likely turned syrupy and sour since Delia had brewed it before heading out before dawn. Delia was a counselor in the mayor’s family justice center where she put in marathon days relocating and counseling victims of domestic violence. She’d been an EMT at Mount Sinai and then did a tour as an Army medic in Iraq. Neither job, she said, had quite prepared her for the work of repairing the minds of six-year-olds who’d had their teeth knocked out and shoulders separated by dads and moms and girlfriends and boyfriends and other transients who stampeded through their lives or convulsed on the floor from overdoses.

René stopped, sipped, grimaced.

“Have you been sitting there all night?” she said.

“No. I took a walk. Came back, watched Atomic Blonde.” He gestured at his laptop nesting in the rumpled sheet on the couch. “Then I called in sick again.”

“What did you tell them, nightmare or breakup?”

“I said I have a migraine.”

“Do you?”

“I don’t think so.”

“If you don’t know, you don’t have one.”

“Like an orgasm,” Gene said, immediately regretting it. René sipped, grimaced.

“Maybe you can help me with something,” she said.

“What? Yeah.”

“We need a reader.”

“A reader,” he said. “Sure.” He didn’t know what that meant but figured it had to be better than sitting on the couch all day. René had been a dancer, her career peaking in a three-year stint on Contact, the entire Broadway run. Within days after the show closed, plantar fasciitis, left heel, set in. Impervious to treatment, it ended her career. She now tutored French and wrote short plays. She drifted into the second bedroom where they had set up a couple of rubber mats, some barbells, a stationary bike, and a contraption that resembled a torture rack that allowed a person to suspend upside down. René said it helped relieve her spinal compression, another remnant of years of gamboling weightlessly across stages that weren’t built for dancers. She turned on her workout song – “Hey Mama” – and, door wide open, commenced her high kicks, which, to Gene, were still stunning.

He pinched the excess flesh at his waist. There was less to take hold of than he expected. That’s something, he thought, until he remembered he’d hardly eaten since leaving Hoboken, and starvation wasn’t the best weight-loss strategy. He pictured Sue on her five a.m. waterfront run, her hair assembled in a perfect topknot that bobbed fetchingly and never broke. Pulling on his shoes, he called to René that he was making a food run, but she was barking out the count for her gut crunches like a drill sergeant and likely didn’t hear him.

The building, a monumental pre-war cube, was mixed use. Their apartment was on the eighth floor, but Gene liked to take the stairs, walking back and forth between the west and east stairwells, and check out the little businesses interspersed among the residences. There were several buyers and sellers of old gold; a repairer of vacuum cleaners; a rug merchant; a day care operation that, based on the drop-off/pick-up activity, was fabulously successful; import/export operations; and a curiously high concentration of personal injury lawyers. Other enterprises were engaged in activities that could not be readily identified by the names on the doors. Delia said the family-run development company that owned the building wanted it to be fully commercial, but had to keep it at twenty percent or else become subject to the IRS’s commercial tax rate. It was clear to anyone who walked around that that threshold had been far exceeded.

After showering, René found Gene sitting at the kitchen table behind a plate of bagels and a tub of green chile cream cheese he purchased at a deli across Myrtle. Two English earthenware plates from a collection that Delia had inherited from their parents were adjacent to folded paper napkins and butter knives. René, thick black hair wet and raked straight back in a basic rockabilly, observed the display.

“Yum,” she commented. She took a chair, placed a bagel on her plate and, with a grave expression, proceeded to aggressively thumb out texts on her phone.

Gene chewed slowly, tasting nothing. He sliced open a second bagel, doubled the cream cheese and still tasted nothing. He wondered if he was in a state of shock or PTSD. He was feeling something, definitely, but he couldn’t put a name to it. It wasn’t as if this was his first failed relationship. In the past, he reacted conventionally, with tears, alcohol, long walks to nowhere, marathon viewings of Breaking Bad and Game of Thrones accompanied by deeply empathetic reactions to every on-screen expression of loss and regret. It was not that Sue was the love of his life. Or was she? Now that, it occurred to him, was something he should have figured out before it was too late.

“Enough,” René announced, putting her phone face down on the table. “We should go.” She hadn’t touched her bagel.

The reading was a five block walk down Myrtle in a desanctified Catholic Church that had been converted into a community center. Gene had been there, he and Sue sitting with Delia to watch René’s previous play. It was about a female Hispanic firefighter the day after 9/11. As the play opens, she walks through theatrical smoke, caked with soot and blood, obviously dead and wandering confused through the afterlife. She finds the audience and assumes that they too were lost in the horror. There are flashbacks, the firefighter – played cleverly by another actor – and her son, the firefighter with her company, the firefighter with her wife. It was heartbreaking stuff, Gene thought, so much so that he had tears in his eyes when they congratulated René after the performance. René, stunned by Gene’s emotion, started crying too. In tears, their friendship was cast.

They walked down the sunny side of Myrtle. Two blocks along, beads of sweat began rolling down the back of Gene’s neck. René’s phone hummed in her bag. Staring straight ahead, she shook her head in annoyance and let it hum.

“What’s the play about?” said Gene.

“Three dykes having a picnic.”

“Three’s a dangerous number.”

René grunted.

The performance space was on the main floor of the church. The old religious icons and statuary had been swept away, gilded frames surrounding bare patches of peeling plaster and Greek style marble pedestals supporting nothing. In the apse, where the altar had stood, a rough stage of unpainted plywood and two-by-fours had been built, flanked by surprisingly plush blue velvet curtains spread wide. On the stage, folding chairs had been opened, and two women sat, talking and then dropping into silence as René and Gene walked up to what had been the nave and joined them. A single overhead spotlight enclosed them in a white upside down cone.

“This is Gene,” said René.

“Gene?” said one of the women. She was youthful, even with long, uniformly grey hair, parted in the middle and flaring out impudently over her shoulders. She was wearing what looked to Gene like a safari outfit.

“With a G,” Gene said.

The woman’s eyes widened as if Gene had just asked her how things were shakin’ on the veldt.

“Some people think it’s with a J,” Gene elaborated.

“This is Amy, she’s directing,” René said, nodding at the woman in the safari suit. “And this is Roxana. I think you’ve met.”

Roxana was the actor who had played the living firefighter in René’s previous production. She flashed a thin smile. Amy handed Gene the script and informed him that he would be reading the lines for Arden, one of the picnickers, who was also a city cop and was being played by an actor who had to go to a funeral. René and Roxana would read the other characters and would perform those roles in the production, Amy continued in a robo voice. The thick walls of the late nineteenth-century building had somewhat insulated the interior from the hot morning outside, but Gene continued to sweat, his shirt now showing a scattering of dark damp dots. He tried to will his hands to stop shaking, mentally refusing to get sick on top of everything else. He turned the pages, searching for Arden’s lines.

“Arden shows up late,” René said helpfully. “On page eleven.”

René and Roxana cruised through their lines, something about joining a lawsuit to clean up pollution in the Gowanus Canal. Gene was staring intently at page eleven but still missed his entrance.

“Arden!” Amy snapped.

Arden: Do you ladies have a picnic permit?

Eve (played by René): Who’s asking?

Arden: An officer of the law.

Eve: Where’s your uniform?

Arden: I’m undercover.

Eve: Picnic vice?

Ophelia (played by Roxana) (feigning fright): Oh, officer, are you going to arrest us?

All three are silent and then together burst into laughter. Arden sits on the picnic blanket and from a plastic grocery bag pulls a bottle of wine, paper cups, and a box of crackers.

The scene progressed. Arden, it seemed, was less enthusiastic about the lawsuit, and proposed that their energies would produce better results by working cooperatively with some of the businesses near the canal. Amy, who had been looking increasingly fretful each time Gene read, finally spoke up.

“Gene with a G, do you think you can get more into character?”

“Pardon?”

“René and Roxana are acting. They need to bounce off acting.”

“I’m a straight guy reading the lines of a gay woman who probably doesn’t want to sound like a woman.”

“So what’s the problem?”

Roxana giggled, prompting a severe look from Amy.

“He’s not an actor, Amy,” said René.

“We still have work to do here.”

“This is just a reading.”

“Really? Opening night is in three weeks. When do you plan to get serious? Do you think your work of literature is going to come together overnight with good vibes?”

“It won’t come together if you keep up the Eric von Stroheim shtick.”

Amy, who had been lounging insolently in her chair, sat up straight and dropped her copy of the script to the floor. Without a word, she walked off the stage, down the nave and, grey tresses flouncing with fury, out of the building.

“And there you have what Amy means by serious,” René commented. “Let’s continue.”

They did, but the discomfort in the air was too thick. René sighed, mumbled “Sorry,” dismounted the stage, and took the same path as Amy out of the church.

“This is not about you,” Roxana said to Gene.

“Me?” said Gene. “Why would it be about me?”

“It’s not.” Roxana stuck her script into a backpack and donned her sunglasses. “Nice seeing you again, Gene with a G. You should get some rest.” She slipped into the shadows and departed by a side door.

He fled, this time on the shaded side of the street, impelled by both his weakness and a dread of learning more than he could deal with, hurrying around parking meters and moms with strollers, turning compulsively to see if René was trailing him.

Outside he saw them, tucked together near one of the church’s faux half columns. René’s face was poised over Amy’s shoulder, blurred a bit by Amy’s electric hair, one arm around her waist, head canted, eyes half closed, lips pursed. When she spotted Gene, René reacted professionally, not too abrupt, hand shifting deliberately to a safer spot on Amy’s forearm, stepping back only half a step and talking at once in a tone that replicated the tension in the church. The change was so smooth that Gene wondered briefly if he imagined what he saw.

She caught up with him in front of their building.

“That wasn’t what it looked like,” René said, breathing hard.

“Ah, more acting.”

“In a way. Amy’s insecure.”

“Frau direktor?”

Her hands flew up, shoulder height, imploring. Gene flinched.

“I need to get this play done, Gene.”

“Showbiz. Of course. What was I thinking?”

It was happening again. He saw it in her eyes and felt it in his. Why oh why did they have to be made from the same mush? But he wasn’t in the mood to bond.

At the building’s door, he turned back.

“I don’t keep secrets from my sister,” he said.

René’s arms were crossed over her chest. She looked small and cold in the fierce midday heat.

“Neither do I.”

In the elevator, he thought about going back to Hoboken. Hadn’t he paid his share of the month’s rent? He still had the key. There had to be a way to just disappear until he was better. He could curl up on the floor of the clothes closet for fuck’s sake. It couldn’t be worse than watching the dissolution of René and Delia or René acting as if nothing had happened or Delia weeping and begging. The more he dwelled on it, the more grotesque the possibilities became. As he took the long walk down the hall, the getaway plan acquired a bit more form and then all at once collapsed as did he the instant he reached Delia’s couch.

She arrived, trembling with her other life, through an ornate doorway that did not belong in the room, but which he somehow knew was oriental and ancient, something she had dragged along with her from her cave of dream plunder. She wore a tattered babushka that covered her forehead but not the rest of her pale crooked face, her pointy nose and chin and the rot of her teeth that he did not see but knew were there. As in the past, she transported around the room, not walking, just reappearing in different spaces, near the bookcase, Gene’s sad pile of possessions, the upholstered chair, another acquisition from their parents that was older than Gene and Delia combined.

“Get out,” he said, or wanted to say, the words evaporating in his throat. But she did hear, turning in automatous jumps to face him.

“I’m not afraid of you,” he said desperately, another thought that had no voice.

“Liar,” she cackled.

All he had to do was move, a leg, an arm, even lift a finger, to break free of her. It’s what he had done the time he was in high school, the night of the day he lacerated his hand in a snow blower, a desperate exertion of will simply to lift his head and pierce the skin of sleep, to see the room without her exotic adornments, to eject her like a glob of bile from his throat, to be awake.

But he couldn’t do it, and now she hovered over him, her thin lips wet and melting. Lifting her dress, she revealed her mottled, stick-like thighs. She straddled his chest and squeezed it between her knees, two shards of glass slowly penetrating his rib cage.

“My little man” she purred, opening her mouth to reveal a bloody hole and with a sound of wind sucked out his breath.

In the morning he lay in their bed, buttressed by more pillows than any two people needed. A scent of lavender, subtle and clean, greeted him along with the faint light of dawn finding the mismatched assortment of thrift shop furniture and the peach colored walls. Slowly, the pieces came together. He was not dead; he could breathe. He remembered Delia rescuing him yet again and, fending off his protests, ushering him into their empty bedroom.

“Dee,” he said. “Something happened.”

“Shush,” she said, placing a finger over his mouth. “I know.”

He felt better. He liked being awake, or maybe he just hated being asleep. But the idea of actually standing slid into his gut and formed into a pool of vileness. Once more, he would have to call in sick, legitimately, not because of a boring personal catastrophe or monstrous dreams, but because he didn’t want to infect his co-workers.

There was a lonely shuffling beyond the door which opened creakily. Delia peeked in, said good morning and sat beside him. The mattress sagged and groaned. There was comfort in that. His big sister, so unchangeably there, a human dreadnaught, who could work thirty hours straight and then play competitive volleyball with kids half her age for all the daylight hours of a summer Sunday at the Prospect Park parade ground. She placed a thermometer under his tongue and fetched a container of Tylenol and a steaming cup of her black brew.

“The caffeine cure?” he said.

“It’ll cheer you up.”

“And keep me up.”

Delia looked thoughtful and then brightened.

“I have something,” she said.

She opened the battered oak wardrobe and stretched for the top shelf and a long cardboard tube. From it she pulled a poster that she pinned to an open space on the wall near the bed.

“Let’s see that dame get past this lineup,” she said.

Gene felt himself smile, the first time in days. The U.S. women’s hockey team, in full pads, smiled back.

“Gotta run,” she said.

“Wait,” he said, reaching blindly for her hand, missing it, and catching her sleeve instead. Their eyes met.

“René,” was all he could say.

Delia smiled sadly, deeply. One by one she plucked away Gene’s fingers before striding across the floor. At the door she stopped and glanced over her shoulder.

“René will be back,” she said. And then she went to work.

On his phone there was a text from Sue. He’d forgotten things, his collection of volcanic rocks, an Ironman watch he didn’t wear anymore and didn’t want. She wrote that she’d bag it all and leave it with the super in Hoboken. He tried to read the CNN news, comprehended nothing and drifted off.

Bass notes, like distant cannon fire, shook him awake. There was a new trapezoid of sunlight on the lime colored sheets. Their bed was a flower garden, lush with surprises. The air vibrated with the music, coming straight through the wall. Of course he knew it, “Hey Mama,” from René’s vintage boombox, big as a cat carrier. He covered his face with a scented pillow. The volume went up, way up. The cannons would not be denied.

“Okay, René,” he laughed under the pillow. “I hear you.”

Bill Schillaci has written short stories off and on for thirty-five years. He has a day job reporting on environmental and worker safety issues and spends his spare time fixing up the old house he and his wife occupy in Ridgewood, New Jersey.